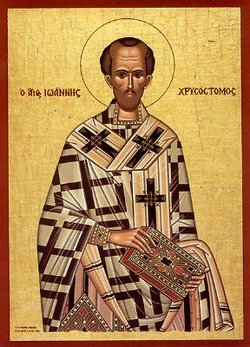

John Chrysostom

Our father among the saints John Chrysostom (347-407), Archbishop of Constantinople, was a notable Christian bishop and preacher from the fourth and fifth centuries in Syria and Constantinople. He is famous for his eloquence in public speaking, his philanthropy, his denunciation of abuse of authority in the Church and in the Roman Empire of the time, and for a Divine Liturgy attributed to him. He had notable ascetic sensibilities. After his death he was named Chrysostom, which comes from the Greek Χρυσόστομος, "golden-mouthed." The Orthodox Church honors him as a saint (feast day, November 13) and counts him among the Three Holy Hierarchs (feast day, January 30), together with Saints Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian. Another feast day associated with him is January 27, which commemorates the event in 437, thirty years after the saint's repose, when his relics were brought back to Constantinople from the place of his death.

John Chrysostom is also recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, which considers him a saint and Doctor of the Church, and by the Church of England, both of whom commemorate him on September 13. His relics were stolen from Constantinople by crusaders in 1204 and brought to Rome, but were returned on November 27, 2004, by Pope John Paul II.

He is sometimes referred to as "John of Antioch," but that name more properly refers to the bishop of Antioch in A.D. 429-441, who led a group of moderate Eastern bishops in the Nestorian controversy.

Contents

Life

He was born in Antioch of noble parents: his father was a high-ranking military officer. His father died soon after his birth and so he was brought up by his mother Anthusa. He was baptized in 370 and tonsured a reader (one of the minor orders of the Church). He began his education under a pagan teacher named Libanius, but went on to study theology under Diodore of Tarsus (one of the leaders of the later Antiochian School) while practising extreme asceticism. He was not satisfied, however, and became a hermit (circa 375) and remained so until poor health forced a return to Antioch.

He was then ordained a deacon in 381 by St. Meletius of Antioch, and was ordained a presbyter in 386 by Bishop Flavian I of Antioch. It seems this was the happiest period of his life. Over about twelve years, he gained much popularity for the eloquence of his public speaking. Notable are his insightful expositions of Bible passages and moral teaching. The most valuable of his works are his Homilies on various books of the Bible. He particularly emphasized almsgiving. He was also most concerned with the spiritual and temporal needs of the poor. He spoke out against abuse of wealth and personal property. In many respects, the following he amassed was no surprise. His straightforward understanding of the Scriptures (in contrast to the Alexandrian tendency towards allegorical interpretation) meant that the themes of his talks were eminently social, explaining the Christian's conduct in life.

One incident that happened during his service in Antioch perhaps illustrates the influence of his sermons best. Around the time he arrived in Antioch, the bishop had to intervene with the Emperor St. Theodosius I on behalf of citizens who had gone on a riotous rampage in which statues of the Emperor and his family were mutilated. During the weeks of Lent in 387, John preached 21 sermons in which he entreated the people to see the error of their ways. These apparently had a lasting impression on the people: many pagans reportedly converted to Christianity as a result of them. In the event, Theodosius' vengeance was not as severe as it might have been, merely changing the legal standing of the city.

In late October of 397, he was called (somewhat against his will) to be the bishop of Constantinople. He deplored the fact that Imperial court protocol would now assign to him access to privileges greater than the highest state officials. During his time as bishop he adamantly refused to host lavish entertainments. This meant he was popular with the common people, but unpopular with the wealthy and the clergy. In a sermon soon after his arrival he said, "people praise the predecessor to disparage the successor." His reforms of the clergy were also unpopular with these groups. He told visiting regional preachers to return to the churches they were meant to be serving—without any pay out.

His time there was to be far less at ease than in Antioch. Theophilus, the Pope of Alexandria, wanted to bring Constantinople under his sway and opposed John's appointment to Constantinople. Being an opponent of Origen's teachings, he accused John of being too partial to the teachings of that master. Theophilus had disciplined four Egyptian monks (known as "the Tall Brothers") over their support of Origen's teachings. They fled to and were welcomed by John. He made another enemy in Aelia Eudoxia, the wife of the eastern Emperor Arcadius, who assumed (perhaps with justification) that his denunciations of extravagance in feminine dress were aimed at herself.

St. John was fearless when denouncing offences in high places. An alliance was soon formed against him by Eudoxia, Theophilus and other enemies of his. They held a synod in 403 to charge John, in which the accusation of Origenism was used against him. It resulted in his deposition and banishment. He was called back by Arcadius almost immediately, however, for the people of the city were very angry about his departure. There was also a "quaking" in the Imperial bedroom (thought to be either an actual earthquake or perhaps as a stillbirth or miscarriage for the empress) which was seen as a sign of God's anger. Peace was shortlived. A silver statue of Eudoxia was erected near the cathedral of Hagia Sophia. John denounced the dedication ceremonies. He spoke against her in harsh terms: "Again Herodias rages; again she is confounded; again she demands the head of John on a charger" (an allusion to the events surrounding the death of John the Forerunner). Once again he was banished, this time to Caucasus in Georgia.

The pope in Rome (Innocent I at this time) protested at this banishment, but to no avail. John wrote letters which still held great influence in Constantinople. As a result of this, he was further exiled to Pityus (on the eastern edge of the Black Sea). However, he never reached this destination, as he died during the journey. His final words were "Glory be to God for all things!"

His importance

During a time when city clergy were subject to much criticism for their high lifestyle, John was determined to reform his clergy at Constantinople. These efforts were met with resistance and limited success. He was particularly noted as an excellent preacher. As a theologian, he has been and continues to be very important in Eastern Christianity, but has been less important to Western Christianity. He generally rejected the contemporary trend for emphasis on allegory, instead speaking plainly and applying Bible passages and lessons to everyday life. In some ways, he represents a sort of synthesis between the hermeneutic methods of the more allegorical Alexandrian School and the more literal Antiochian School.

His banishments demonstrated that secular powers had strong influence in the eastern Church at this period in history. They also demonstrated the rivalry between Constantinople and Alexandria, both of which wanted to be recognized as the preeminent eastern see. This mutual hostility would eventually lead to much suffering for the Church and the Eastern Empire. Meanwhile in the West, Rome's primacy had been unquestioned from the fourth century onwards. An interesting point to note in the wider development of the papacy is the fact that Innocent's protests availed nothing, demonstrating the lack of influence the bishops of Rome held in the East at this time.

Quotes

"In the matter of piety, poverty serves us better than wealth, and work better than idleness, especially since wealth becomes an obstacle even for those who do not devote themselves to it. Yet, when we must put aside our wrath, quench our envy, soften our anger, offer our prayers, and show a disposition which is reasonable, mild, kindly, and loving, how could poverty stand in our way? For we accomplish these things not by spending money but by making the correct choice. Almsgiving above all else requires money, but even this shines with a brighter luster when the alms are given from our poverty. The widow who paid in the two mites was poorer than any human, but she outdid them all."

"For Christians above all men are forbidden to correct the stumblings of sinners by force...it is necessary to make a man better not by force but by persuasion. We neither have autority granted us by law to restrain sinners, nor, if it were, should we know how to use it, since God gives the crown to those who are kept from evil, not by force, but by choice."

"When an archer desires to shoot his arrows successfully, he first takes great pains over his posture and aligns himself accurately with his mark. It should be the same for you who are about to shoot the head of the wicked devil. Let us be concerned first for the good order of sensations and then for the good posture of inner thoughts."

"Even if we have thousands of acts of great virtue to our credit, our confidence in being heard must be based on God's mercy and His love for men. Even if we stand at the very summit of virtue, it is by mercy that we shall be saved."

"Why do you beat the air and run in vain? Every occupation has a purpose, obviously. Tell me then, what is the purpose of all the activity of the world? Answer, I challenge you! It is vanity of vanity: all is vanity."

On Serving the Poor

“[N]othing is so strong and powerful to extinguish the fire of our sins as almsgiving. It is greater than all other virtues. It places the lovers of it by the side of the King Himself, and justly. For the effect of virginity, of fasting … is confined to those who practice them, and no other is saved thereby. But almsgiving extends to all, and embraces the members of Christ, and actions that extend their effects to many are far greater than those which are confined to one. For almsgiving is the mother of love, of that love, which is the characteristic of Christianity, which is greater than all miracles, by which the disciples of Christ are manifested. It is the medicine of our sins, the cleansing of the filth of our souls, the ladder fixed to heaven; it binds together the body of Christ.” (Homily 6 on Titus)

“And well does [Saint Paul] … having made mention of almsgiving, call 'it grace,' now indeed saying, "Moreover, brethren, I make known to you the grace of God bestowed on the Churches of Macedonia;" and now, "they of their own accord, praying us with much entreaty in regard of this grace and fellowship:" and again, "that as he had begun, so he would also finish in you this grace also." For this is a great good and a gift of God; and rightly done assimilates us, so far as may be, unto God; for such an one is in the highest sense a man. . . Greater is this gift than to raise the dead. For far greater is it to feed Christ when hungry than to raise the dead by the name of Jesus: for in the former case you do good to Christ, in the latter He to you. And the reward surely comes by doing good, not by receiving good. For here indeed, in the case of miracles I mean, you are God's debtor. In that of almsgiving, you have God for a debtor. Now it is almsgiving, when it is done with willingness, when with bountifulness, when you deem yourself not to give but to receive, when done as if you were benefitted, as if gaining and not losing; for so this were not a grace.” (Homily 16 on 2 Corinthians)

"Do you wish to see his altar?… This altar is composed of the very members of Christ, and the body of the Lord becomes your altar… venerable because it is itself Christ's body… You venerate the altar of the church when the body of Christ descends there. But you neglect the other who is himself the body of Christ, and remain indifferent to him when he dies of hunger. This altar you can see lying everywhere, in the alleys and in the markets, and you can sacrifice upon it anytime… And as the priest stands, invoking the Spirit, so do you too invoke the Spirit, not by words, but by deeds.” (Homily 20 on 2 Corinthians)

“When then you see a poor believer, think that you behold an altar: when you see … a beggar, not only insult him not, but even reverence him.” (Homily 20 on 2 Corinthians)

“Because he is a poor man, feed him; because Christ is fed.” (Homily 48 on Matthew)

“I beseech you, let us be imitators of Christ: in this regard it is possible to imitate Him: this makes a man like God: this is more than human. Let us hold fast to Mercy: she is the schoolmistress and teacher of that higher Wisdom. He that has learned to show mercy to the distressed, will learn also not to resent injuries; he that has learned this, will be able to do good even to his enemies. Let us learn to feel for the ills our neighbors suffer, and we shall learn to endure the ills they inflict.” (Homily 14 on the Acts of the Apostles)

“There is no sin, which alms cannot cleanse, none, which alms cannot quench: all sin is beneath this: it is a medicine adapted for every wound.” (Homily 25 on the Acts of the Apostles)

“Where alms are, the devil dares not approach, nor any other evil thing.” (Homily 45 on Acts)

“If you ever wish to associate with someone, make sure that you do not give your attention to those who enjoy health and wealth and fame as the world sees it, but take care of those in affliction, in critical circumstances, who are utterly deserted and enjoy no consolation. Put a high value on associating with these, for from them you shall receive much profit, and you will do all for the glory of God. God Himself has said: ‘I am the father of orphans and the protector of widows.’ ” (Baptismal Instructions 6.12)

On Wealth

“…the rich man did not take Lazarus’ money, but failed to share his own…indeed this also is theft, not to share one’s possessions [with the poor]… For our money is the Lord’s, however we may have gathered it. . . The rich man is a kind of steward of the money which is owed for distribution to the poor… Therefore, let us use our goods sparingly, as belonging to others…How shall we use them sparingly, as belonging to others? When we do not spend beyond our needs, and do not spend for our needs only, but give equal shares into the hands of the poor.” (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“Charity is so called because we give it even to the unworthy.” (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“The poor man has one plea, his want and his standing in need: do not require anything else from him; but even if he is the most wicked of all men and is at a loss for his necessary sustenance, let us free him from hunger.” (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“The almsgiver is a harbor for those in necessity: a harbor receives all who have encountered shipwreck, and frees them from danger; whether they are bad or good or whatever they are who are in danger, it escorts them into his own shelter. So you likewise, when you see on earth the man who has encountered the shipwreck of poverty, do not judge him, do not seek an account of his life, but free him from his misfortune.” (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“Need alone is a poor man’s worthiness… We show mercy on him not because of his virtue but because of his misfortune, in order that we ourselves may receive from the Master His great mercy, in order that we ourselves, unworthy as we are, may enjoy His philanthropy. For if we were going to investigate the worthiness of our fellow servants, and inquire exactly, God will do the same for us. If we seek to require an accounting from our fellow servants, we ourselves will lose the philanthropy from above: ‘For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged,’ He says” (Matthew 7:2). (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“Not to share our own wealth with the poor is theft from the poor and deprivation of their means of life; we do not possess our own wealth, but theirs. If we have this attitude, we will certainly offer our money; and by nourishing Christ in poverty here and laying up great profit hereafter, we will be able to attain the good things which are to come, by the grace and kindness of our Lord Jesus Christ…” (Second sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“I do not despise anyone; even if he is only one, he is a human being, the living creature for whom God cares. Even if he is a slave, I may not despise him; I am not interested in … his condition as master or slave, but his soul. Even if he is only one, he is a human being, for whom the heaven was stretched out, the sun appears, the moon changes, the air was poured out, the springs gush forth, the sea was spread out, the prophets were sent, the law was given—and why should I mention all these?—for whom the only-begotten Son of God became man. My Master was slain and poured out His blood for this man. Shall I despise him?” (Sixth sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

“Wealth will be good for its possessor if he does not spend it only on luxury…; if he enjoys luxury in moderation and distributes the rest to the stomachs of the poor, then wealth is a good thing.” (Seventh sermon on Lazarus and the rich man)

On Evangelism

“There is nothing to weigh against a soul, not even the whole world. So that although thou give countless treasure unto the poor, you will do no such work as he who converts one soul. . . A great good it is, I grant, to have pity on the poor; but it is nothing equal to the withdrawing them from error. For he that does this resembles Paul and Peter: we being permitted to take up their Gospel, not with perils such as theirs — with endurance of famines and pestilences, and all other evils, (for the present is a season of peace;) — but so as to display that diligence which comes of zeal. For even while we sit at home, we may practice this kind of fishery. Who has a friend or relation or inmate of his house, these things let him say, these do; and he shall be like Peter and Paul. And why do I say Peter and Paul? He shall be the mouth of Christ. For [Christ] says, “He that takes forth the precious from the vile shall be as My mouth.” (Jeremiah 15:19) And though thou persuade not today, tomorrow you shall persuade. And though thou never persuade, you shall have your own reward in full. And though thou persuade not all, a few out of many persuade all men; but still they discoursed with all, and for all they have their reward. For not according to the result of the things that are well done, but according to the intention of the doers, is God wont to assign the crowns; though thou pay down but two farthings, He receives them; and what He did in the case of the widow, the same will He do also in the case of those who teach. Do not thou then, because you cannot save the world, despise the few; nor through longing after great things, withdraw yourself from the lesser. If you cannot a hundred, take thou charge of ten; if you cannot ten, despise not even five; if you cannot five, do not overlook one; and if you cannot one, neither so despair, nor keep back what may be done by you. Do you see not how, in matters of trade, they who are so employed make their profit not only of gold but of silver also? For if we do not slight the little things, we shall keep hold also of the great. But if we despise the small, neither shall we easily lay hand upon the other. Thus individuals become rich, gathering both small things and great. And so let us act; that in all things enriched, we may obtain the kingdom of heaven; through the grace and loving-kindness of our Lord Jesus Christ, through Whom and with Whom unto the Father together with the Holy Spirit be glory, power, honor, now and henceforth and for evermore. Amen.” (3rd Homily on 1 Corinthians)

The Homilies against the Judaizers

Chrysostom wrote of the Jews and of Judaizers in eight homilies Adversus Judaeos (against the Judaizers).[1] At the time he delivered these sermons, Chrysostom was a tonsured reader and had not yet been ordained a priest or bishop.

- "The festivals of the pitiful and miserable Jews are soon to march upon us one after the other and in quick succession: the feast of Trumpets, the feast of Tabernacles, the fasts. There are many in our ranks who say they think as we do. Yet some of these are going to watch the festivals and others will join the Jews in keeping their feasts and observing their fasts. I wish to drive this perverse custom from the Church right now." (Homily I, I, 5)

- "Shall I tell you of their plundering, their covetousness, their abandonment of the poor, their thefts, their cheating in trade? The whole day long will not be enough to give you an account of these things. But do their festivals have something solemn and great about them? They have shown that these, too, are impure." (Homily I, VII, 1)

- "But before I draw up my battle line against the Jews, I will be glad to talk to those who are members of our own body, those who seem to belong to our ranks although they observe the Jewish rites and make every effort to defend them. Because they do this, as I see it, they deserve a stronger condemnation than any Jew." (Homily IV, II, 4)

- "Are you Jews still disputing the question? Do you not see that you are condemned by the testimony of what Christ and the prophets predicted and which the facts have proved? But why should this surprise me? That is the kind of people you are. From the beginning you have been shameless and obstinate, ready to fight at all times against obvious facts." (Homily V, XII, 1)

The purpose of these attacks was to prevent Christians from joining with Jewish customs, and thus prevent the erosion of Chrysostom's flock. Robert L. Wilken contends that applying the modern label of Anti-Semitism onto St. John Chrysostom is anachronistic. He particularly focuses on the rhetorical genre that St. John employed in these homilies, and points out that St. John was using the genre of psogos (or invective):

- "The psogos was supposed to present unrelieved denigration of the subject. As one ancient teacher of rhetoric put it, the psogos is "only condemnation" and sets forth only the "bad things about someone" (Aphthonius Rhet. Graeci 2.40).... In psogos, the rhetor used omission to hide the subject's good traits or amplification to exaggerate his worsts features, and the cardinal rule was never to say anything positive about the subject. Even "when good things are done they are proclaimed in the worst light" (Aristides Rhet. Graeci 2.506). In an encomium, one passes over a man's faults in order to praise him, and in a psogos, one passed over his virtues to defame him. Such principles are explicit in the handbooks of the rhetors, but an interesting passage from the church historian Socrates, writing in the mid fifth century, shows that the rules for invective were simply taken for granted by men and women of the late Roman world. In discussing Libanius's [St. John's Pagan instructor in Rhetoric] orations in praise of the emperor Julian [the Apostate], Socrates explains that Libanius magnifies and exaggerates Julian's virtues because he is an "outstanding sophist" (Hist. eccl. 3.23). The point is that one should not expect a fair presentation in a psagos, for that is not its purpose. The psogos is designed to attack someone, says Socrates, and is taught by the sophist in the schools as one of the rudiments of their skills.... Echoing the same rhetorical background, Augustine said that, in preparing an encomium on the emperor, he intended "that it should include a great many lies," and that the audience would know "how far from the truth they were" (Conf. 6.6)." (p. 112).[2]

Another important point of context that Wilkens highlights is the reign of Julian the Apostate, and the way he used the Jews (and was used by them) to undercut Christianity. Julian had even planned to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, primarily because he believed it would refute Christ's prophesies about the destruction of the Temple. This happened when St. John was a young man, and so Christians at this time had no reason to believe that they had a firm position in society that could not be overturned in a short period of time. Thus polemics against the Jews were not the polemics of a group with a firm grip on power, but the polemics of a group that had reason to fear what the future might bring.

- "The Roman Empire in the fourth century was not the world of Byzantium or medieval Europe. The institutions of traditional Hellenic culture and society were still very much alive in John Chrysostom's day. The Jews were a vital and visible presence in Antioch and elsewhere in the Roman Empire, and they continued to be a formidable rival to the Christians. Judaizing Christians were widespread. Christianity was still in the process of establishing its place within the society and was undermined by internal strife and apathetic adherents. Without an appreciation of this setting, we cannot understand why John preached the homilies and why he responds to the Judaizers with such passion and fervor. The medieval image of the Jew should not be imposed on antiquity. Every act of historical understanding is an act of empathy. When I began to study John Chrysostom's writings on the Jews, I was inclined to judge what he said in light of the unhappy history of Jewish-Christian relations and the sad events in Jewish history in modern times. As much as I feel a deep sense of moral responsibility for the attitudes and actions of Christians toward the Jews, I am no longer ready to project these later attitudes unto the events of the fourth century. No matter how outraged Christians feel over the Christian record of dealing with the Jews, we have no license to judge the distant past on the basis of our present perceptions of events of more recent times' [3]

See also: Was Saint John Chrysostom Anti-Semitic?

Work on liturgy

Two of his writings deserve special mention. He harmonized the liturgical life of the Church by revising the prayers and rubrics of the Divine Liturgy, or celebration of the Holy Eucharist. To this day, the Orthodox Church typically celebrates the Divine Liturgy of John Chrysostom, together with Roman Catholic churches that are in the Eastern or Byzantine rites (i.e., Uniates). These same churches also read his Paschal Homily at every Pascha, the greatest feast of the Church year.

Thus, Orthodox Christians throughout the world participate in St. John's Divine Liturgy nearly every week and hear his famous Paschal Homily at every Pascha.

Hymns

Troparion (Tone 8)

- Grace shining forth from your lips like a beacon has enlightened the universe.

- It has shown to the world the riches of poverty;

- it has revealed to us the heights of humility.

- Teaching us by your words, O Father John Chrysostom,

- intercede before the Word, Christ our God, to save our souls!

Kontakion (Tone 6)

- Having received divine grace from heaven,

- with your mouth you teach all men to worship the Triune God.

- All-blest and venerable John Chrysostom,

- we worthily praise you, for you are our teacher, revealing things divine!

| John Chrysostom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Nectarius |

Archbishop of Constantinople 398–404 |

Succeeded by: Arsacius of Tarsus |

Notes

- ↑ "This [Adversus Iudaeos] is the Latin translation of the title given to the homilies in PG 48.843. The Benedictine editor, Montfaucon, gives a footnote (reprinted ibid.) which states that six MSS and [Henry] Savile [in his edition (1612) of Chrysostom] have at the head of this homily: "A discourse against the Jews; but it was delivered against those who were Judaizing and keeping the fasts with them [i.e., the Jews]." This note is not altogether accurate because Savile, for Hom. 27 of Vol. 6 (which is Disc. I among the Adversus Iudaeos in PG and in this translation), gives (p. 366) the title: "Chrysostom's Discourse Against Those Who Are Judaizing and Observing Their Fasts." In Vol. 8 (col. 798) Savile states that he has emended Hoeschel's edition of this homily with the help of two Oxford MSS, one from the Corpus Christi College and the other from the New College; he must have gotten his title from any or all of these sources. Savile gives all eight of the homilies Adverus Iudaeos (Vol. 6.312-88) but in the order IV-VIII (wich are entitled Kata Ioudaion, i.e. Adversus Iudaeos), I (with the title given above), III and II (with the title affixed to them in our translation). Because of the titles in both some MSS and editions and because of the arguments which will be set forth in this introduction, we feel justified in calling this work Against Judaizing Christians rather than giving it the less irenic and somewhat misleading traditional title Against the Jews." John Chrysostom, Discourses against Judaizing Christians, translated by Paul W. Harkins. The Fathers of the Church; v. 68 (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1979), p. xxxi, footnote 47

- ↑ John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century, by Robert L. Wilken (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1983), p. 112.

- ↑ John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century, by Robert L. Wilken (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1983), pp. 162-163.

Source

- Some material taken from John Chrysostom at Wikipedia

Modern Bibliography

- On Wealth and Poverty (SVS Press, 1999) (ISBN 088141039X)

- On Marriage and Family Life (SVS Press, 1986) (ISBN 0913836869)

- Robert Van de Weyer, On Living Simply: The Golden Voice of John Chrysostom (Triumph Books, 1997) (ISBN 0764800566)

- Holy Apostles Convent, The Lives of the Three Great Hierarchs: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom (Holy Apostles Convent Pubns, 2001) (ISBN 0944359116)

See also

External links

- Works about and by John Chrysostom from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- Quotes from St. John Chrysostom - Orthodox Church Quotes website

- John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople (GOARCH)

- Removal of the Relics of John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople (GOARCH)

- St. John Chrysostom the Archbishop of Constantinople (OCA)

- Repose of St John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople (OCA)

- Translation of the relics of St John Chrysostom the Archbishop of Constantinople (OCA)

- November 13, 2004 : The Martyrdom of Saint John Chrysostom (Antiochian)

- A few beautiful icons of St. John Chrysostom

- John I Chrysostom - Church of Constantinople website

French

- Abbaye Saint-Benoît de Port-Valais. SAINT JEAN CHRYSOSTOME - OEUVRES COMPLÈTES.

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > OrthodoxWiki > Featured Articles

Categories > People > Clergy > Bishops

Categories > People > Clergy > Bishops

Categories > People > Clergy > Bishops > Bishops by century > 4th-5th-century bishops

Categories > People > Clergy > Bishops > Bishops by city > Patriarchs of Constantinople

Categories > People > Monastics

Categories > People > Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Byzantine Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Church Fathers

Categories > People > Saints > Church Fathers > Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

Categories > People > Saints > Saints by century > 5th-century saints