American Orthodox Catholic Church

| This article forms part of the series Orthodoxy in America | |

| |

| History | |

| American Orthodox Timeline American Orthodox Bibliography Byzantines on OCA autocephaly Ligonier Meeting ROCOR and OCA | |

| People | |

| Saints - Bishops - Writers | |

| Jurisdictions | |

| Antiochian - Bulgarian OCA - Romanian - Moscow ROCOR - Serbian Ecumenical Patriarchate: | |

| Monasteries | |

| Seminaries | |

| Christ the Saviour Holy Cross Holy Trinity St. Herman's |

St. Tikhon's St. Sava's St. Sophia's St. Vladimir's |

| Organizations | |

| Assembly of Bishops AOI - EOCS - IOCC - OCEC OCF - OCL - OCMC - OCPM - OCLife OISM - OTSA - SCOBA - SOCHA | |

| Groups | |

| Amer. Orthodox Catholic Church Brotherhood of St. Moses the Black Evangelical Orthodox Church Holy Order of MANS/CSB Society of Clerks Secular of St. Basil | |

| Edit this box | |

The American Orthodox Catholic Church (in full, The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America) was the first attempt by mainstream Orthodox canonical authorities at the creation of an autocephalous Orthodox church for North America. It was chartered in 1927 by Metropolitan Platon (Rozhdestvensky), primate of the Russian Metropolia and his holy synod, and its history in any real sense as part of the mainstream Orthodox Church ended in 1934. During its short existence, it was mainly led by Aftimios Ofiesh, Archbishop of Brooklyn.

Contents

A Promising Beginning

Fr. Serafim Surrency's book, The Quest for Orthodox Church Unity in America (1973) begins its account of the formation of this body thus:

- Starting in 1927 the first move was initiated to found a canonical American Orthodox Church with the blessing of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church and with the hope that world Orthodoxy would recognize the legitimacy of the new body. The initiative for this attempt belonged to Bishop Aftimios (Ofiesh) of Brooklyn and a member of the Council of Bishops in his capacity as Diocesan for the Syrians (Arabs) which acknowledged the authority of the Russian Church (pp. 32-33).

In this project, Aftimios had the assistance of two American-born Orthodox clerics who had been ordained to the priesthood in the early 1920s, Hieromonk Boris (Burden) and Priest Michael Gelsinger. Both men were particularly concerned about the loss of Orthodox young people to the Roman Catholic and Episcopal churches in the US—the Episcopal Church was of special concern, as it was a liturgical church in some ways similar to Orthodoxy and generally enjoyed a special status of prestige in American society.

At the outset, the new venture appeared quite successful—within the space of only four years, with the support of the synod of the Russian Metropolia, four bishops were consecrated and an impressive charter was granted from said synod, titled An Act of the Synod of Bishops in the American Dioceses of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The charter itself—referencing the authority of a letter from Metr. Sergius (locum tenens of the Patriarchate of Moscow) which indicated that autonomous Orthodox churches could be founded outside Russia—granted to the new church body the full name The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America, with The American Orthodox Catholic Church as its "short name." Additionally,

- We hereby, on this 2nd day of February (new Style) in the year 1927, charge one of our number, His Eminence the Most Reverend Aftimios, Archbishop of Brooklyn, with the full responsibility and duty of caring and providing for American Orthodoxy in the especial sense of Orthodox Catholic people born in America and primarily English-speaking or any American residents or parishes of whatever nationality or linguistic character or derivation not satisfactorily provided with proper and canonical Orthodox Catholic care, ecclesiastical authority, teaching and ministrations of the Church or who may wish to attach themselves by the properly and legally provided means to an autonomous, independent, American Orthodox Catholic Church.... a distinct, independent, and autonomous branch of the Orthodox Catholic Church... (pp. 34-35).

Signed by the entire Metropolia synod at the time—Metr. Platon, Aftimios, Theophilus, Amphilohy, Arseny, and Alexy—it further named Aftimios as the primate of the new church and elected and gave order for "the Consecration of the Very Reverend Leonid Turkevitch to be Bishop in the newly-founded [church]... as assistant to its Governing Head..." (p. 35). Fr. Leonid eventually did get consecrated to the episcopacy, though not in the new church body, and is better known as Metr. Leonty (Turkevich) of New York, primate of the Russian Metropolia. His refusal at the time was based mainly on a "press of family obligations" which led to his insistence on "a specific stipulated salary which could not be met" (p. 36). To replace Fr. Leonid as the first assistant to Aftimios, Platon chose Archimandrite Emmanuel (Abo-Hatab), who was consecrated on September 11, 1927, by Aftimios, assisted by Theophilus and Arseny.

The constitution which was drawn up for the church by the Metropolia is twenty-eight pages long and quite detailed, indicating a great deal of thought went into its drafting. Though it was dated December 1 of 1927, it was not made public until the following spring. Two significant passages are noted by Fr. Serafim in his book. From Article III: "This Church is independent (autocephalous) and autonomous in its authority in the same sense and to the same extent as are the Orthodox Patriarchates of the East and the Autocephalous Orthodox Churches now existing." From Article IV: "This Church has original and primary jurisdiction in its own name and right over all Orthodox Catholic Christians of the Eastern Churches and Rite residing or visiting in the United States, and Alaska and the other territories of the United States, in Canada, Mexico, and all North America" (p. 37). Fr. Serafim then comments:

- "To anyone knowledgeable in Canon Law, these two sections just quoted are absurd. Not only did the Russian Bishops under Metr. Platon—whose own relationship to the Mother Church was abnormal—not only have not have any authority to set up an autocephalous Church but obviously by the logic of the 2nd Section quoted, Metr. Platon and his Bishops should have subordinated themselves to the new Head of the North American Church, Archbishop Aftimios... One can safely say that Metr. Platon (perhaps with the exception of Archbishop Aftimios) and his Bishops never had any intention of granting any such broad and unlimited authority and jurisdiction and indeed this may well have been a factor which turned Metr. Platon against the new Church soon after its very inception (ibid.).

Reaction and Opposition

The reaction against the establishment of the new church was "swift and negative," especially from the Karlovsty Synod (ROCOR), with whom the Metropolia had broken ties shortly before in 1926 and who viewed itself as the Metropolia's rightful canonical authority. (See: ROCOR and OCA.)

- In letters dated the 27th of April and the 3rd of May 1927, the Synod made clear their unalterable opposition to the formation of the new Church both on the grounds that Metr. Platon and his Bishops had no power or authority to authorize the founding of the new Church (it must be kept in mind that for almost two years now there had been a break between Metr. Platon and the Exile Synod) as well as on the grounds that there was no justification or rationale for the establishment of an American Orthodox Church, at that time or at any time in the foreseeable future (p. 37).

Aftimios himself answered in June with "an equally forceful reply," denouncing the Karlovsty synod as "the uncanonical pseudo-Synod of the Outlandish Russian Orthodox Church," forbidding his clergy and faithful from having anything to do with them (ibid.). Like his estranged former associates in ROCOR, Metr. Platon himself almost immediately turned his back on his ecclesiastical daughter and became "increasingly unreliable in supporting the new Church," mainly because of its continual publication of "hard line" articles in the Orthodox Catholic Review (edited by Hieromonk Boris and Priest Michael) aimed at the Episcopal Church. In a letter to Aftimios, Platon wrote: "'I must attest before Your Eminence that without their (American Episcopalian) entirely disinterested and truly brotherly assistance our Church in America could not exist' and concluded his letter by asking Abp Aftimios to order Father Boris to cease his 'steppings out' against the Protestant Episcopalians" (p. 38).

To further worsen matters, in 1924, Archbishop Victor (Abo-Assaley) was sent to America by the Church of Antioch and then began to encourage Orthodox Arabs to come under Antiochian jurisdiction rather than that of the Russians or the new American church. He did not, however, make much headway in his endeavors. In 1928, Aftimios and his group mainly focussed on the establishment of their church's legal status and had some initial success. On May 26, another bishop was consecrated, Sophronios (Beshara) as bishop of Los Angeles, given responsibility "not only for the parishes who still considered themselves within the jurisdiction of the Russian Mission but also those parishes who comprise a part of the new Church and as a Missionary Bishop as well he was responsible for all territory west of the Mississippi River" (ibid.). However,

- With three Bishops the fledgling Church would appear to have achieved a solid foundation—but such was not the case. It became more and more apparent that Metr. Platon had changed his mind about the wisdom of attempting to establish an American Orthodox Catholic Church. Not only were some of his Episcopalian allies against the new venture but it was increasingly clear that no recognition for the new Church would be forthcoming from any Autocephalous Church. In any case it is known that Metr. Platon categorically forbade Archpriest Leonid Turkevitch to accept consecration in the new Church (pp. 38-39).

Early in 1929, Aftimios attempted to gain support with the Greek archbishop Alexander (Demoglou), the first primate of the newly formed Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America. The archbishop's response was that he had authority over not only all the Greek Orthodox in America but over all Orthodox Christians there. They were apparently "vexed over the fact that the Reverend Demetrius Cassis, an American of Greek parentage, had been ordained by Abp Aftimios for the new American Church" (p. 38).

Open Hostility

Fr. Serafim believes that Platon's opposition to the new church had shifted from veiled to "quite open and above board," because Aftimios, in a letter dated October 4, 1929, declared that:

- "His Eminence, the Most Reverend Platon (Rozhdestvensky), the Metropolitan of Khersson and Odessa, has no proper, valid, legal, or effective appointment, credentials or authority to rule the North American Archdiocese of the Russian Orthodox Church in any capacity. Such being the case it follows that from the departure of His Eminence Archbishop Alexander (Nemolovsky) that the lawful and canonical ruling headship of the Archdiocese of the Aleutian Islands and North America in the Patriarchal Russian Church has naturally been vested in the First Vicar and Senior Bishop in this Jurisdiction" therefore "the title and position of 'Metropolitan of North America and Canada' has no canonical existence in the Russian Church." It is signed by "Aftimios, First Vicar and Senior Bishop in the Archdiocese of the Aleutian Islands and North America" (p. 39).

Aftimios no doubt had in mind as he wrote such a letter that Platon had, at least in writing, already given him authority over all Orthodox Christians in North America. Fr. Serafim continues and says that Aftimios's denunciation of Platon's authority had "little or no effect" in the Russian parishes and on their clergy; "presumably they knew of the 1924 Ukaz of Patriarch Tikhon suspending Platon but specifying that he was to continue to rule the Archdiocese until such time as a Bishop was sent to relieve him" (ibid.). The announcement also had a negative effect on some members of the American Orthodox Catholic Church, as well, because two weeks after its being made public, Bp. Emmanuel (Abo-Hatab) requested canonical release from Aftimios (who reluctantly gave it) and then went over to Platon and with his direction tried to bring Syrian parishes away from Aftimios and back under the Metropolia.

Despite these troubles Aftimios nevertheless explored new opportunities and began negotiations to bring Bp. Fan (Noli) to the US from Germany to serve as a bishop in his church with jurisdiction over Albanian Orthodox Christians. (Bp. Fan eventually did come to America, but under the auspices of the Metropolia.) Aftimios continued to attempt to shore up his jurisdiction's legitimacy:

- Deserted by the Russian Bishops under Metr. Platon, with two rival Syrian Bishops, we find Abp Aftimios appealing to the successor of Greek Archbishop Alexander, Archbishop Damaskinos "as the special Representative and Exarch of the Ecumenical Throne of Constantinople" in view of the "present chaotic and helpless state of the Church of Russia" that the "Holy Great Church which you represent" could "bring about a united and disciplined Orthodoxy in America for greater and more profit to Orthodoxy than any other settlment of the Hellenic divisions in this country" (p. 40).

At nearly the same time (October of 1930), Aftimios sent a letter to his clergy indicating they were to keep their distance from Bp. Germanos (Shehadi) of Zahle, who had come from Antioch (without its authorization) mainly to attempt to gather funds from Arabic Orthodox parishes but had also worked at encouraging such parishes to come under Antioch's jurisdiction. While in America, he also accepted under his omophorion one Archpriest Basil Kherbawi, "one of the most zealous and loyal priests of the Syrian Mission of the Russian jurisdiction who had been suspended by Abp Aftimios for disloyalty" (ibid.).

Disintegration

In 1932, by a decision of a New York State court, Aftimios's cathedral was taken from him and given over to the Metropolia, as its charter stated that it could only be used by a hierarch subject to the authority of the Russian church. Nevertheless, Aftimios consecrated two more bishops, Ignatius (W.A.) Nichols (a former Episcopal cleric who had become an Old Catholic episcopus vagans), and Joseph (Zuk) for the Ukrainians, who had the allegiance of perhaps a half dozen such parishes.

Armed with new bishops at his side but probably quite discouraged over the state of his jurisdiction both internally and externally, Aftimios then made the decision which probably was the death-knell for the American Orthodox Catholic Church:

- ...on the 29th of April 1933 Abp Aftimios, in defiance of all Orthodox Tradition and Canon Law... married in a civil ceremony to a young Evangelical Syrian girl born in America [she was actually a member of the Syrian Orthodox parish in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania]—and despite all the efforts of responsible parties, he refused to resign as Archbishop of the new Church (p. 41).

Three days after Aftimios's wedding, the two new bishops of the church, Ignatius and Joseph, held a "synod meeting" by themselves, and believing that Aftimios had resigned, elected Joseph as the new "President Archbishop of the Church" with Ignatius being his designated successor. They further voiced their support of Aftimios's marriage, stating that "'inasmuch as it is merely a Canon of the European and Asiatic branches of the Holy Eastern Orthodox Church, that a Bishop should not be married, such has no valid weight on the American Church where conditions are dramatically opposite' and 'therefore the Holy North American Synod congratulates His Eminence on the moral courage in the step he has taken'" (ibid.). Fr. Serafim then observes: "This new thunderbolt was sufficient to effectively eliminate any authority the new Church might still claim to have—particularly when there were only six parishes by the summer of 1933 still adhering to the new Church" (ibid.).

Joseph later denied making the agreement with Ignatius, "but he was already a sick man (and died on the 23rd of February 1934)" (ibid.). Ignatius then got married himself in June of 1933 and began entering into relations with the representatives of the Living Church in America (the Soviet-sponsored pseudo-church), which had been competing (especially legally) with the jurisdiction of the Metropolia and the ROCOR. He eventually broke relations even with the Living Church and returned to being an episcopus vagans, dying as the pastor of a small Community Church in Middle Springs, Vermont, but not before starting multiple small religious bodies, many of whom claim apostolic succession from him.

The only bishop left to the American Orthodox Catholic Church was Sophronios (Beshara), who then appealed to Platon for assistance and had also intended to contact Emmanuel (Abo-Hatab), but was deterred from doing so when Emmanuel died on May 29, 1933, being buried by Platon (his gravestone reads May 30). "Bp Sophronius, despite all the setbacks, seemed to take his new post as 'President Locum Tenens of the American Holy Synod' quite seriously, and although he wished to restore relations with Metr. Platon, he wanted to be accepted as an equal Head of a Church" (p. 42). Platon was focussed primarily at that point on the arrival from Russia of the representative of the Patriarchate, Bp. Benjamin (Fedchenkov), who had been sent to investigate the ecclesiastical status of Orthodox America. Thus Platon "felt he could not concern himself with the crumbling new Church and so the remaining priests and parishes wandered from one authority to another or became completely independent," with the exceptions of Hieromonk Boris and Priest Michael, who were received back into the authority of Moscow and the Metropolia, respectively.

Later in 1933, Sophronios officially removed and suspended Aftimios in October and deposed Ignatius in November. He still refused to submit to Platon or the Patriarchate, however: "Despite the efforts of Bishop Benjamin and Hieromonk Boris, Bp Sophronius refused to consider being subordinate to Bishop Benjamin although he would have been allowed a considerable amount of independence and would have been permitted to continue to live on the West Coast" (ibid.).

The end of the "Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America" came when Sophronios died in 1934 in Los Angeles. (Fr. Serafim gives the date of his death as 1934, though his gravestone reads 1940.) He is now buried at the Antiochian Village in Pennsylvania alongside St. Raphael of Brooklyn and Emmanuel (Abo-Hatab).

Analysis

Fr. Serafim's analysis of the failure of this church is as follows:

- There can be no question that while the movers of the new Church were sincere and highly motivated that nonetheless they were fostering an idea whose time had not yet come, or to use more appropriate phraseology: Almighty God in his infinite wisdom did not see fit to bless this first attempt to have an American Orthodox Church. On the human level it is clear why the movement did not succeed. The Orthodox in America were still in their own particular ghettos... [the church] was unable to attract or find clergy theologically trained in the Orthodox tradition and able to communicate with the young people with immigrant parents (p. 33).

External pressures on the movement also contributed to its demise:

- While the Russian Council of Bishops gave initial support, it was only moral support, and the first person elected to be a Hierarch of the new Church in fact turned down the nomination because it was not possible to guarantee him any kind of salary—which is indicative of another primary deficiency of the movement, no adequate financing.... [The] new Church lost its most important supporter, Metr. Platon, because of antagonism of the clergy initiators towards the Protestant Episcopal Church.... [some of whose authorities] resented the American Orthodox Church as being a challenge to... the "senior Orthodox Church in America" [i.e., the Episcopal Church], and that pressure was put on Metr. Platon to withdraw his support or the financial assistance he was receiving from the Episcopal Church... would be cut off and perhaps he would be deprived of the use, on a temporary basis, of Episcopal churches (pp. 33-34).

Nevertheless,

- ...it would be most unjust to blame the failure of the "Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America" solely or even primarily on Protestant Episcopal opposition. One can state it more strongly: the various Orthodox groups in America at that time simply were not ready in terms of church consciousness for the establishment of an American Orthodox Church (p. 34).

Epilogue

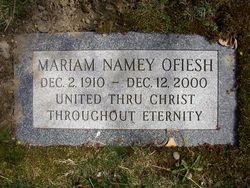

Aftimios Ofiesh lived in relative obscurity with his wife Mariam Namey Ofiesh, fathering a son named Paul, who eventually became a Presbyterian elder in Mountaintop, Pennsylvania.[1] After living in Wilkes-Barre and New Castle, towns in Pennsylvania, the Ofiesh family finally settled in Kingston (near Wilkes-Barre). In 1937 he was asked by parishioners in Allentown to return to active leadership in the Orthodox Church and made one unsuccessful effort in response. Members of his wife's family in Wilkes-Barre record that he continued to dress as a bishop and was called by some of them "Uncle Sayedna." He died in Kingston on July 24, 1966, a few months before his 86th birthday, leaving instructions that he should be buried quietly without any clergy.

In 1995, an independent group claiming the corporate rights to the names "The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America" (THEOCACNA) and "American Orthodox Catholic Church" (AOCC), regarding the church itself as having been "held in Locum Tenens due to lack of clergy" from 1966 to 1995[2], formed a new holy synod and included Mariam Namey Ofiesh (whom they regarded as the locum tenens) among the members of its board of directors. It has since declared itself successively a metropolitanate (1997) and then a patriarchate (2003). In 1999 it suffered a major internal schism when four of its bishops broke from it and claimed the name for themselves. In the same year, Mrs. Ofiesh retired from the board and departed this life the following year.

In 2007, the group threatened canonical punishment against those who hold the mainstream interpretation of the history of the American Orthodox Catholic Church (i.e., that Aftimios was deposed, the jurisdiction dissolved, etc.)[3]. Much of the group's website is dedicated to claims of their legal and canonical authenticity and especially to their registration of various names and service marks.

Sources

- Damick, Rev. Andrew Stephen. The Archbishop's Wife: Archbishop Aftimios Ofiesh of Brooklyn, the American Orthodox Catholic Church, and the Founding of the Antiochian Archdiocese (1880-1943) (M.Div. thesis, St. Tikhon's Orthodox Theological Seminary, 2007).

- Gabriel, Archpriest Antony. The Ancient Church on New Shores: Antioch in North America (San Bernardino, California: St. Willibrord's Press, 1996), 44-55.

- LaBat, Sean J. The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America - 1927-1934, A Case Study in North American Missions (M.Div. thesis, St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary, 1995).

- Ofiesh, Mariam Namey. Archbishop Aftimios Ofiesh (1880-1966): A Biography Revealing His Contribution to Orthodoxy and Christendom (Sun City West, AZ: Abihider Co., 1999). (ISBN 0966090810)

- Surrency, Archim. Serafim. The Quest for Orthodox Church Unity in America (New York: Sts. Boris and Gleb Press, 1973), 32-42.

- The Life of Archbishop Aftimios Ofiesh, from the 1995 THEOCACNA group (an altered form of an article by Fr. John W. Morris which appeared in the February and March 1981 issues of The Word)

External link

- THEOCACNA, the 1995 group