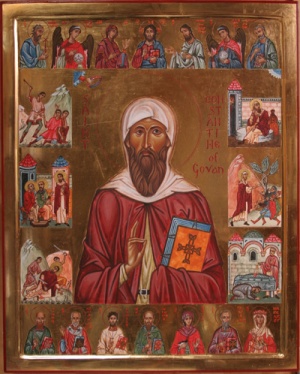

Constantine of Cornwall and Govan

Saint Constantine of Cornwall, also Constantine of Dumnonia, Constantine III of Britain, Saint Custennin, Custennin ap Cado, Custennin ap Cadwr,[1] Costentyn or Constantine of Govan (ca. 520-576 AD)[2][3] is a 6th century Cornish saint that is identified with a minor British king Constantine, who came to repentance at St Davids monastery in Wales, after a life of vice. It is maintained that he went from Wales to Ireland, and from there went as a missionary to the Picts in Scotland, where he was martyred by pirates at Cantyre (Kintyre); however there are difficulties with this latter part of his hagiography involving a conflation of events with one (or two) other 'Constantines'.

His feast day is observed on March 9,[2][3][4] in the tradition of Cornwall and Wales, and on March 11[5][6][7] in the Scottish and Irish traditions. Two places in Cornwall are still named after him today.[4]

It is possible that the British king (†576)[2] is not the same person as the Scottish martyr (†576,[8] or †590[6]).[note 1] To add to the ambiguity there is another saint from a slightly later period, King Constantine of Strathclyde (†640), whose feast day is on March 11 as well, but who is said to have reposed in peace (i.e. not martyred),[9] and whose life has been inextricably conflated with the Scottish king-martyr. Therefore the traditions of St. Constantine of Cornwall (identified with the Scottish martyr of the same date), and St. Constantine of Strathclyde are very much confused. Canon G.H. Doble in his Cornish Saints says that “the name has given rise altogether to one of the most fearful series of muddles in the whole history of hagiography.”[10][note 2]

Contents

Life

Constantine of Cornwall probably succeeded his father, Cador, as King of Dumnonia in the early 6th century. Literary tradition indicates AD 537, after the Battle of Camlann from which, some sources say, "Sir Constantine" was the only survivor.[3] He is reputed to have been married to the daughter of the King of Brittany and to have led a life full of vice and greed until he was led to conversion by Saint Petroc:

One day, while out hunting a deer, his prey took shelter in St. Petroc's cell. So impressed was the King by the saint's power that he and his body guard immediately converted to Christianity. Constantine gave Petroc an ivory hunting horn in commemoration of the event and this was long revered along with the Saint's other relics at Bodmin. The King became co-founder of this famous Cornish monastery.[3]

After the death of his queen he resigned the crown to his son, in order to take up the religious life himself.

He moved amongst his people, founding churches at the two Constantines, near Padstow and Falmouth, and at Illogan; also at Milton Abbot and Dunsford in Devon. Later, he travelled across the Bristol Channel to join St. Dewi (David) at Mynyw (St. Davids), where he resided as a monk for many years. He founded the church at Cosheston, near Pembroke, but eventually settled as a hermit in Costyneston (Cosmeston) near Cardiff. He may have died there, though there are persistent stories that he travelled still further north and preached to the people of Galloway before being martyred in Kintyre on 9th March AD 576.[3]

However according to Bishop Richard Challoner's hagiography of "Saint Constantine, Prince and Priest", in Britannia Sancta (1745), as listed in William Canon Fleming's A Complete History of the British Martyrs (1902):

Martyred at Cantyre, in Scotland, on March 11th, 590.

"The Scottish Breviaries commemorate on March 11th the Feast of Saint Constantine, Martyr. He is said to have been a prince who, after the death of his princess, retired from the world, and, having resigned his kingdom to his son, became a monk in the Monastery of Saint David's. Going afterwards to Ireland, he entered a religious house at St. Carthag at Rathene, where, unknown to any, he served for four years at a mill, until his name was discovered. He was then fully instructed, ordained priest, and sent as a missionary to the Picts in Scotland. Having for many years laboured with Saint Columba for their conversion, he established a religious community of men at Govan, and converted the inhabitants of Cantyre to Christianity. At length the happiness he so long desired came to him in his advanced age; he was slain by infidels actuated by hatred of the Christian religion."[6]

Sources

Gildas

The only contemporary information about him comes from Gildas, writing in 547 AD, who mentions Constantine in chapters 28 and 29 of his work De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae.[11][12] He is one of five Brythonic kings whom the author rebukes and compares to Biblical beasts. Constantine is called the "tyrannical whelp of the unclean lioness of Damnonia". This Damnonia is generally associated with the kingdom of Dumnonia, a Brythonic kingdom in Southwestern Britain.[13] However, it is possible that Gildas was instead referring to the territory of the Damnonii in what was later known as the Hen Ogledd or "Old North". Gildas says that despite swearing an oath against deceit and tyranny, Constantine disguised himself in an abbot's robes and attacked two "royal youths" praying before a church altar, killing them and their companions.[note 3] Gildas is clear that Constantine's sins were manifold even before this, as he had committed "many adulteries" after casting off his lawfully wedded wife. Gildas encourages Constantine, whom he knows to still be alive at the time, to repent his sins lest he be damned.[11][12]

Life of Saint Petroc

The Life of Saint Petroc mentions a Constantine who was converted to Christianity by that holy man at nearby Little Petherick after the deer Constantine was hunting took shelter with him.

Life of Saint David

A Constantine "King of the Cornishmen" also appears in the Life of Saint David as having given up his crown in order to enter this saint's monastery at St David's in Wales.

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Much later, Geoffrey of Monmouth included the figure in his pseudohistorical chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae, adding fictional details to Gildas' account and making Constantine the successor to King Arthur as King of Britain. Under the influence of Geoffrey, derivative figures appeared in a number of later works.

Annals of Ulster

The conversion of a Constantine[note 4] in 588 AD is also recorded in the Annals of Ulster.

Breviary of Aberdeen

A Constantine also appears in the Breviary of Aberdeen as entering a monastery in Ireland incognito before joining Saint Mungo (alias Kentigern) and becoming a missionary to the Picts.

Veneration

South-west Britain

The two major centers for the cult of Saint Constantine (of Dumnonia) were the church in Constantine Parish, and the Chapel of Saint Constantine in St Merryn Parish (now Constantine Bay), both in Cornwall.[14] Both of these may have originally supported monastic establishments, although this has been challenged.[note 5]

The saint at Constantine Bay was almost certainly the 'wealthy man' of this name mentioned in the Life of Saint Petroc. The ruined chapel at Constantine Bay also has a nearby holy well, uncovered in 1911. Taking the waters there was said to bring rain during dry weather. The chapel's splendid font is now in the parish church at St Merryn.

In addition, Constantine's name is given to the parish church of Milton Abbot in Devon, as well as to extinct chapels in Illogan and Dunterton.

The saint's day is generally celebrated on March 9, and an annual "Feast" is held in the village of Constantine, on the Sunday nearest to March 9.

Scotland and Ireland

English archaeologist and historian C. A. R. Radford has said that the Constantine whose shrine is at Govan, and the Constantine connected to an important church in the Deanery of Desnes (Diocese of Galloway) are possibly different men, although the two are inextricably conflated in the hagiographical literature.[15]

Hymns

Troparion - Tone 5[16]

Grieving at the loss of thy young spouse,

thou didst renounce the world, O Martyr Constantine,

but seeing thy humility God called thee to leave thy solitude and serve Him as a priest.

Following thy example,

we pray for grace to see that we must serve God as He wills

and not as we desire,

that we may be found worthy of His great mercy.

Kontakion - Tone 4[16]

Thou wast born to be King of Cornwall,

O Martyr Constantine,

and who could have foreseen that thou wouldst become the first hieromartyr of Scotland.

As we sing thy praises, O Saint,

we acknowledge the folly of preferring human plans to the will of our God.

See also

Notes

- ↑ If it is to be argued that the Scottish martyr Constantine is a separate individual from the Cornish Saint Constantine, then perhaps he was a King of Damnonia (Strathclyde) not Dumnonia (Cornwall); however this is guesswork and there is no way to tell for certain. The Great Synaxaristes (in the Greek) includes an entry for March 9 for "St Constantine the Martyr of Cornwall" (†576), and another entry for May 9 for a "St Constantine the Martyr, King of the Scots" (†576), with the exact same death date for both. It also has a third entry for March 11 for "St Constantine the King" of Strathclyde (†640).

- ↑ In "The De Excidio of Gildas: Its Authenticity and Date" by Thomas O’Sullivan, it has been suggested that "probably two or three Constantines have been confused", and quotes the judgment of Canon G. H. Doble that:

- “…there is not the smallest evidence that Constantine of Gildas is the St. Constantine whom we find honoured in the five parishes of Devon and Cornwall, as some persons, forgetful of the fact that Constantine was a very common name at the time, have rashly assumed.”

- (Thomas D. O'Sullivan. The De Excidio of Gildas: Its Authenticity and Date. BRILL, 1978. p.95.)

- “…there is not the smallest evidence that Constantine of Gildas is the St. Constantine whom we find honoured in the five parishes of Devon and Cornwall, as some persons, forgetful of the fact that Constantine was a very common name at the time, have rashly assumed.”

- ↑ "According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, these were, in fact, the treacherous sons of the evil usurper, Mordred, who were killed in Winchester & London."

- (David Nash Ford's Early British Kingdoms (EBK). St. Constantine of Cornwall, King of Dumnonia (c.AD 520-576). Nash Ford Publishing, 2001.)

- ↑ "Conversion," be it noted is a term which may apply either to the acceptance of the Christian faith or to the adoption of monastic life.

- ↑ Dr. Lynette Olson (1989) has challenged Charles Henderson's assertion (Henderson 1937) that there was a monastic establishment at Constantine, Kerrier, Cornwall.

References

- ↑ Anthony Richard Birley. The People of Roman Britain. University of California Press, 1980. p.210.

- Cites: P.C. Bartrum. Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts. Cardiff: University of Wales, 1966. p.179.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Κωνσταντίνος ὁ Μάρτυρας ὁ τῆς Κορνουάλλης. 9 Μαρτίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ. (†576)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 David Nash Ford's Early British Kingdoms (EBK). St. Constantine of Cornwall, King of Dumnonia (c.AD 520-576). Nash Ford Publishing, 2001.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Latin Saints of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Rome. Constantine March 9.

- ↑ Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). March 11 - St. Constantine, Martyr. The Lives of the Saints. Volume III: March. 1866. (Bartleby.com)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 William Canon Fleming (Rector of St. Mary’s, Moorsfields, London). A Complete History of the British Martyrs – From the Roman Occupation to Elizabeth’s Reign. Proprietors of the Catholic Repository. Little Britain, London, 1902. (pp. 19,141,145)..

- Cites: Challoner's Britannia Sancta (Meighan, 1745).

- ↑ Katherine I. Rabenstein. March 11 - Constantine of Scotland M (AC). St. Patrick Catholic Church, Washington, D.C. - Saint of the Day.

- ↑ Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Κωνσταντίνος ὁ Μάρτυρας βασιλέας τῶν Σκώτων. 9 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Κωνσταντίνος ὁ βασιλεὺς. 11 Μαρτίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ Constantine, Cornwall. (The Constantine website, serving the community of Constantine in Cornwall).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, ch. 28–29.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Giles, John Allen, ed. (1841). The Works of Gildas and Nennius. London: James Bohn — English translation.

- ↑ Lloyd, John Edward. A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1912.

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas. The Saints of Cornwall. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0198207654

- ↑ C. A. Ralegh Radford (Fellow of the British Academy). "The Early Church In Strathclyde and Galloway". Medieval Archaeology, 11 (1967), pp.105-126. p.118.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. Constantine of Scotland - King & Martyr. Feast day: March 11 (+576).

Sources

Hagiographies (March 9th)

- Great Synaxaristes: (Greek)

Ὁ Ἅγιος Κωνσταντίνος ὁ Μάρτυρας ὁ τῆς Κορνουάλλης. 9 Μαρτίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ. (†576)

- Latin Saints of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Rome. Constantine March 9.

- Vladimir Moss. MARTYR CONSTANTINE OF CORNWALL. St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church (McKinney (Dallas area) Texas).

- (Celebrated March 9 in Wales and Cornwall; March 11 in Scotland; and March 18 in Ireland)

- David Nash Ford's Early British Kingdoms (EBK). St. Constantine of Cornwall, King of Dumnonia (c.AD 520-576). Nash Ford Publishing, 2001.

- Constantine_of_Cornwall. Reference.com.

- Rev. Charles William Boase (C.W.B). St. Constantinus (5). In: William Smith and Henry Wace (Eds.). A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines. Volume 1: A-D. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1877. p.660.

Hagiographies (March 11th)

- Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. Constantine of Scotland - King & Martyr. Feast day: March 11 (+576).

- Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). March 11 - St. Constantine, Martyr. The Lives of the Saints. Volume III: March. 1866. (Bartleby.com)

- William Canon Fleming (Rector of St. Mary’s, Moorsfields, London). A Complete History of the British Martyrs – From the Roman Occupation to Elizabeth’s Reign. Proprietors of the Catholic Repository. Little Britain, London, 1902. (pp. 19,141,145). (†590)

- Katherine I. Rabenstein. March 11 - Constantine of Scotland M (AC). St. Patrick Catholic Church, Washington, D.C. - Saint of the Day.

Hagiography (May 9th)

- Great Synaxaristes: (Greek)

Ὁ Ἅγιος Κωνσταντίνος ὁ Μάρτυρας βασιλέας τῶν Σκώτων. 9 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ. (†576)

- (Saint Constantine the Martyr, King of the Scots, May 9).

Wikipedia

- (Lists: "Custennin ap Cado (probably Saint Custennin) (c.530–c.560)")

Monographs

- Henderson, Charles and G. H. Doble (Ed.). A history of the parish of Constantine in Cornwall. Truro: Royal Institution of Cornwall, 1937.

- Gilbert Hunter Doble. The Saints of Cornwall. Volumes 1-4. Printed for the Dean and Chapter of Truro by Parrett & Neves, 1960. ISBN 9781861430472

- Nicholas Orme. The Saints of Cornwall. Oxford University Press US, 2000. ISBN 9780198207658

- Anthony Richard Birley. The People of Roman Britain. University of California Press, 1980.

External Links

- Constantine, Cornwall. (The Constantine website, serving the community of Constantine in Cornwall).

- Constantine III of Britain explained. Everything.Explained.At.

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > People > Rulers

Categories > People > Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Martyrs

Categories > People > Saints > Pre-Schism Western Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Saints by century > 6th-century saints

Categories > People > Saints > Saints of the British Isles