Difference between revisions of "Russian Orthodox Mission in China"

m (link) |

m |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

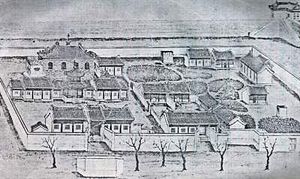

| − | The '''Russian Orthodox Mission in China''', also known as the '''Russian Ecclesiastical Mission''', was the effort by [[Church of Russia]] to bring Orthodox Christianity to China. The mission | + | [[Image:RusMissionChina.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Compound of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing, China]] |

| + | |||

| + | The '''Russian Orthodox Mission in China''', also known as the '''Russian Ecclesiastical Mission''', was the effort by [[Church of Russia]] to bring Orthodox Christianity to China. The mission originated in the seventeenth century after the forces of Chinese Emperor Kangxi (Kang Hsi) brought Russian captives, including an Orthodox [[priest]], to Beijing, China after the capture of the Russian fortress Albasin. The Mission continued until the [[Church of China]] formed in 1956 after the Communist Chinese government required the departure of non-Chinese church officials. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | The Russian Orthodox Mission in China had its beginnings with the capture of forty-five Russians when the Chinese Emperor Kangxi (Kang Hsi), of the Qing dynasty, captured Albasin, a Russian fortress on the Amur River. Among those captured was Fr. Maxim Leontev, an Orthodox priest. He was brought with the prisoners to Beijing late in the year 1685. There he settled in the ambassadorial quarters in the north eastern section of the city and served his small community for twenty years, using a converted Chinese temple as his [[chapel]]. The chapel was [[consecration of a church|consecrated]] to the [[Holy Wisdom]] of God. In 1695, Fr. Maxim received documentation from the [[Metropolitan]] of Tobolsk recognizing the consecration of the church and directed Fr. Maxim to commemorate the Chinese emperor and to begin preaching to the Chinese. Fr. Maxim reposed in 1712, thus ending his informal mission. | + | {{OrthodoxyinChina}} |

| + | The Russian Orthodox Mission in China had its beginnings with the capture of forty-five Russians when the Chinese Emperor Kangxi (Kang Hsi), of the Qing dynasty, captured Albasin, a Russian fortress on the Amur River. Among those captured was Fr. [[Maxim Leontev]], an Orthodox priest. He was brought with the prisoners to Beijing late in the year 1685. There he settled in the ambassadorial quarters in the north eastern section of the city and served his small community for twenty years, using a converted Chinese temple as his [[chapel]]. The [[chapel]] was [[consecration of a church|consecrated]] to the [[Holy Wisdom]] of God. In 1695, Fr. Maxim received documentation from the [[Metropolitan]] of Tobolsk recognizing the consecration of the church and directed Fr. Maxim to commemorate the Chinese emperor and to begin preaching to the Chinese. Fr. Maxim reposed in 1712, thus ending his informal mission. | ||

| − | With Fr. Maxim’s passing, a formal Orthodox Mission was formed that acted as official representative of the Russian government. The activities of the mission were subordinated to the Russian government diplomatic and political interests This period lasted until 1860. During this period the composition and head of the mission changed about every ten years and was generally composed of four [[clergy]] and six [[laymen]]. The laymen were usually students whose duty was to learn the Chinese and Manchu languages and then became interpreters and eventually consuls for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The mission was financed by and received direction from the government. This situation directly affected the [[missionary]] activities of the clergy. As the relations between Russia and China were defined formally, the work of each member of the mission was clearly defined. Under such circumstances, the missionary efforts of the Mission were greatly hindered and conversions, | + | With Fr. Maxim’s passing, a formal Orthodox Mission was formed that acted as the official representative of the Russian government. The activities of the mission were subordinated to the Russian government diplomatic and political interests. This period lasted until 1860. During this period the composition and head of the mission changed about every ten years and was generally composed of four [[clergy]] and six [[laity|laymen]]. The laymen were usually students whose duty was to learn the Chinese and Manchu languages and then became interpreters and eventually consuls for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The mission was financed by, and received direction from the government. This situation directly affected the [[missionary]] activities of the clergy. As the relations between Russia and China were defined formally, the work of each member of the mission was clearly defined. Under such circumstances, the [[missionary]] efforts of the Mission were greatly hindered and the number of conversions, evident in the small number of baptisms, was not significant. |

Each change of the head of the mission has been identified serially. During the period to 1860 the number of changes was thirteen. Beijing being on the end of a long caravan route, communications with Russia were infrequent, only two to four times each year. This hampered the receipt of funds for the operation of the Mission. | Each change of the head of the mission has been identified serially. During the period to 1860 the number of changes was thirteen. Beijing being on the end of a long caravan route, communications with Russia were infrequent, only two to four times each year. This hampered the receipt of funds for the operation of the Mission. | ||

| − | Although hampered as missionaries by the political limitations, the succession of [[archimandrite]]s and [[bishop]]s who headed the Mission successfully introduced the cultural, ethnographical, and statistical information to Europeans through translations of Chinese literature. Among these works were the translations and compositions of Fr. Ioakinf (Bichurin) and a Chinese dictionary by Fr. Daniel Siviloff | + | Although hampered as [[missionaries]] by the political limitations, the succession of [[archimandrite]]s and [[bishop]]s who headed the Mission successfully introduced the cultural, ethnographical, and statistical information to Europeans through translations of Chinese literature. Among these works were the translations and compositions of Fr. [[Iakinf (Bichurin) of Beijing|Ioakinf (Bichurin)]] and a Chinese dictionary by Fr. Daniel Siviloff. During this 150 year period the Russian Orthodox Mission was confined to the mission center in Beijing. This confinement resulted in less than two hundred conversions of Chinese which included many who were descendants of the Albasin prisoners. |

| − | The Treaty of Tianjin (Tientsin) in 1858 changed the situation of the Beijing mission radically. The treaty admitted to China representatives of foreign governments and rights of residence in China to Christian missionaries. In the new period diplomatic and religious activities of the Beijing Mission were separated. Translations of the Scriptures began to appear. The Mission head, Archimandrite Gury Karpov, participated actively in the negotiations of the Beijing Treaty of 1860 under which Russia gained lands along the Amur River. Having studied Chinese for many years he was active also in translating the New Testament into Chinese, as well as collecting earlier translations of Orthodox books for re-translation into the Chinese spoken language. He expanded preaching and lecturing in church, reaching areas beyond Beijing. | + | The Treaty of Tianjin (Tientsin) in 1858 changed the situation of the Beijing mission radically. The treaty admitted to China representatives of foreign governments and rights of residence in China to Christian [[missionaries]]. In the new period diplomatic and religious activities of the Beijing Mission were separated. Translations of the Scriptures began to appear. The Mission head, Archimandrite [[Gury (Karpov)]], participated actively in the negotiations of the Beijing Treaty of 1860 under which Russia gained lands along the Amur River. Having studied Chinese for many years he was active also in translating the New Testament into Chinese, as well as collecting earlier translations of Orthodox books for re-translation into the Chinese spoken language. He expanded preaching and lecturing in church, reaching areas beyond Beijing. |

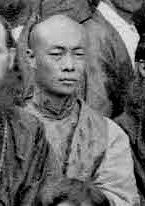

[[Image:MitrophanJiJul1882.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Fr Mitrophan Ji at the All Japan Council of 1882 after his ordination as priest]] | [[Image:MitrophanJiJul1882.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Fr Mitrophan Ji at the All Japan Council of 1882 after his ordination as priest]] | ||

| − | While the literary and translation efforts continued through most of the later part of the nineteenth century, the missionary work in the later part of the century lagged due to inadequate funding for preaching outside of Beijing as well as the arrival of new missionaries whose Chinese language skills were inadequate. The era of an all-Russian [[clergy]] ended when a Chinese priest, Fr. Mitrophan Ji, was [[ordination|ordained]] in Japan by [[Nicholas of Japan| | + | While the literary and translation efforts continued through most of the later part of the nineteenth century, the [[missionary]] work in the later part of the century lagged due to inadequate funding for preaching outside of Beijing, as well as the arrival of new [[missionaries]] whose Chinese language skills were inadequate. The era of an all-Russian [[clergy]] ended when a Chinese priest, Fr. Mitrophan Ji, was [[ordination|ordained]] in Japan by [[Nicholas of Japan|Bp. Nicholas]] of Tokyo on [[June 29]], 1882. Fr. Mitrophan died a [[martyr]] in the [[June 11]], 1900 Boxer uprising in China. The nearly 500 baptisms that had been performed by the Mission and the establishment of two new churches, one each in Hankou and Kalgan (Zhangjiakou) had not contributed significantly to the Mission’s [[missionary]] efforts. |

| − | With the arrival of Archimandrite [[Innocent (Figurosky) of Beijing|Innocent]] in March 1897 the situation | + | With the arrival of Archimandrite [[Innocent (Figurosky) of Beijing|Innocent]] in March 1897 the situation changed abruptly. Fr. Innocent immediately undertook reforms in the Mission: he established a monastery, instituted daily services in Chinese, established support for Albasins with business abilities, organized parish activities, dispatched preachers to the hither lands outside Beijing to spread the [[Gospel]], and established charity efforts among the local poor. While Fr. Innocent’s arrival began a period of active [[missionary]] efforts, the beginning of the twentieth century also brought serious troubles for the Russian Orthodox Mission, as it did for other Christian missions. The Boxer (Yihetuan Movement) revolt in 1900 resulted in the destruction of the buildings in Beijing, Dongdingan, and Kalgan (Zhangjiakou). The riots caused the death of more than 200 Orthodox faithful. The losses also included the extensive library in the Beijing compound begun by Archimandrite Peter during the tenth mission. The Mission survived, and by 1902 there were 32 churches in China with nearly 6,000 members |

Rising out of the ruins of the Boxer revolt, a new Mission attitude was established through the efforts of Fr. Innocent and with the support of the [[Holy Synod]] in Russia. Having been recalled to St. Petersburg for consultations concerning the mission, Fr. Innocent was consecrated bishop and returned to Beijing as Bishop of Beijing in August 1902, with jurisdiction over all the churches along the Chinese-Eastern Railway. | Rising out of the ruins of the Boxer revolt, a new Mission attitude was established through the efforts of Fr. Innocent and with the support of the [[Holy Synod]] in Russia. Having been recalled to St. Petersburg for consultations concerning the mission, Fr. Innocent was consecrated bishop and returned to Beijing as Bishop of Beijing in August 1902, with jurisdiction over all the churches along the Chinese-Eastern Railway. | ||

| − | Rebuilding the mission began immediately, funded by the Chinese government | + | Rebuilding the mission began immediately, funded by the Chinese government as compensation for the damages caused by the Boxer Revolt. Additionally, nearly all of China was opened to [[missionary]] work. New churches and chapels began to appear. A church and school were opened in Yongpingfu in Zhili province. Also in Zhili province some twenty chapels were opened by a Chinese priest. In Weihuifu, a church and school were founded through the gratitude of a Henan province official who had received protection from Russians during the revolt. |

| − | By 1916, the Russian Orthodox Mission in China had grown greatly. In Beijing, three monasteries were established: Dormition Monastery, the Hermitage of the Exaltation of the Cross in Xishan (Western Hills near Beijing), and a women’s monastery. There were nineteen churches including four in Beijing and 32 missions including 14 in Zhili province, 12 in Hebei, four in Henan, one in Xi’anfu, and one in Mongolia. The Mission also controlled 17 schools for boys and three for girls. In addition the Mission maintained a number of institutions | + | By 1916, the Russian Orthodox Mission in China had grown greatly. In Beijing, three monasteries were established: Dormition Monastery, the Hermitage of the Exaltation of the Cross in Xishan (Western Hills near Beijing), and a women’s monastery. There were nineteen churches including four in Beijing and 32 missions including 14 in Zhili province, 12 in Hebei, four in Henan, one in Xi’anfu, and one in Mongolia. The Mission also controlled 17 schools for boys and three for girls. In addition the Mission maintained a number of institutions relating to the publication of books, and various work shops. |

Evangelization of Chinese increased, and by 1916 the number of baptized Chinese numbered 5,587, including 583 who were baptized in 1915. The vast majority of teachers in the Mission schools were Chinese. | Evangelization of Chinese increased, and by 1916 the number of baptized Chinese numbered 5,587, including 583 who were baptized in 1915. The vast majority of teachers in the Mission schools were Chinese. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 35: | ||

In 1956, in fulfillment of agreements between the Soviet Union and Communist China, the Moscow Patriarchate granted autonomy to the Church of China formally ending the Russian Mission in China. At that time the Church of China had two Chinese bishops, a number of priests, and an estimated 20,000 faithful. Having remained under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate, Abp. Victor of Beijing, the last Russian bishop in China and leader of the last Spiritual Mission departed for the Soviet Union in 1956, closing the three hundred year old Russian Orthodox Mission in China. | In 1956, in fulfillment of agreements between the Soviet Union and Communist China, the Moscow Patriarchate granted autonomy to the Church of China formally ending the Russian Mission in China. At that time the Church of China had two Chinese bishops, a number of priests, and an estimated 20,000 faithful. Having remained under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate, Abp. Victor of Beijing, the last Russian bishop in China and leader of the last Spiritual Mission departed for the Soviet Union in 1956, closing the three hundred year old Russian Orthodox Mission in China. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Currently, the site of the mission in the district of Dongzhimen (Eastern Straight Gate) of Beijing is occupied by the Embassy of Russia. | ||

==Heads of mission== | ==Heads of mission== | ||

===Period of diplomatic representatives=== | ===Period of diplomatic representatives=== | ||

| − | *First mission (1716-1728). Archimandrite Ilarion (Lezhaisky) Reposed in Beijing in 1717. | + | *First mission (1716-1728). Archimandrite [[Ilarion (Lezhaisky)]] Reposed in Beijing in 1717. |

*Second mission (1729-1735). Archimandrite Antony (Platkovsky). | *Second mission (1729-1735). Archimandrite Antony (Platkovsky). | ||

*Third mission (1736-1745). Archimandrite Illarion (Trusov). Reposed in Beijing in 1741. | *Third mission (1736-1745). Archimandrite Illarion (Trusov). Reposed in Beijing in 1741. | ||

| Line 47: | Line 52: | ||

*Eleventh mission (1830-1840). Hieromonk (later Archimandrite) Veniamin (Morachevich). | *Eleventh mission (1830-1840). Hieromonk (later Archimandrite) Veniamin (Morachevich). | ||

*Twelfth mission (1840-1849). Archimandrite Policarp (Tugarinov). | *Twelfth mission (1840-1849). Archimandrite Policarp (Tugarinov). | ||

| − | *Thirteenth mission (1850-1858). Archimandrite Pallady (Kafarov). Also led the fifteenth mission. | + | *Thirteenth mission (1850-1858). Archimandrite [[Pallady (Kafarov) of Beijing|Pallady (Kafarov)]]. Also led the fifteenth mission. |

| − | ===Period of limited missionary activities=== | + | ===Period of limited [[missionary]] activities=== |

*Fourteenth mission (1858-1864). Archimandrite Gury (Karpov). In 1866, consecrated vicar Bishop of Cheboksary, Kazan Eparchy; In 1867, Bishop of Tauria and Simferopol; 1881, Archbishop; Reposed in 1882. | *Fourteenth mission (1858-1864). Archimandrite Gury (Karpov). In 1866, consecrated vicar Bishop of Cheboksary, Kazan Eparchy; In 1867, Bishop of Tauria and Simferopol; 1881, Archbishop; Reposed in 1882. | ||

*Fifteenth mission (1865-1878). Archimandrite Pallady (Kafarov). Reposed in 1878 in Marseilles during return to Russia due to illness. | *Fifteenth mission (1865-1878). Archimandrite Pallady (Kafarov). Reposed in 1878 in Marseilles during return to Russia due to illness. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 67: | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Church of China]] | *[[Church of China]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

*[http://www.orthodox.cn/localchurch/1685-1745.txt Russian Mission in China 1685-1745 ] | *[http://www.orthodox.cn/localchurch/1685-1745.txt Russian Mission in China 1685-1745 ] | ||

*[http://www.orthodox.cn/localchurch/beijing/18thcentmission2_en.txt Russian Mission in China 1745-1755] | *[http://www.orthodox.cn/localchurch/beijing/18thcentmission2_en.txt Russian Mission in China 1745-1755] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further Reading== | ||

| + | * Eric Widmer. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=3ZjnRS1g6zkC The Russian ecclesiastical mission in Peking during the eighteenth century]. Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1976. 262 pp. | ||

| + | : (ISBN 0674781295; ISBN 9780674781290) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Sources== | ||

| + | *[http://orthodox.cn/localchurch/1610romc_en.htm Russian Orthodox Mission in China] | ||

| + | *[http://www.cs.ust.hk/faculty/dimitris/metro/orth_china.html Orthodoxy in China] | ||

| + | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orthodoxy_in_China Wikipedia: Chinese Orthodox Church] | ||

[[Category: Dioceses]] | [[Category: Dioceses]] | ||

[[Category: Church History]] | [[Category: Church History]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Orthodoxy in China]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[ro:Misiunea Ortodoxă Rusă în China]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:13, May 29, 2020

The Russian Orthodox Mission in China, also known as the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, was the effort by Church of Russia to bring Orthodox Christianity to China. The mission originated in the seventeenth century after the forces of Chinese Emperor Kangxi (Kang Hsi) brought Russian captives, including an Orthodox priest, to Beijing, China after the capture of the Russian fortress Albasin. The Mission continued until the Church of China formed in 1956 after the Communist Chinese government required the departure of non-Chinese church officials.

Contents

History

The Russian Orthodox Mission in China had its beginnings with the capture of forty-five Russians when the Chinese Emperor Kangxi (Kang Hsi), of the Qing dynasty, captured Albasin, a Russian fortress on the Amur River. Among those captured was Fr. Maxim Leontev, an Orthodox priest. He was brought with the prisoners to Beijing late in the year 1685. There he settled in the ambassadorial quarters in the north eastern section of the city and served his small community for twenty years, using a converted Chinese temple as his chapel. The chapel was consecrated to the Holy Wisdom of God. In 1695, Fr. Maxim received documentation from the Metropolitan of Tobolsk recognizing the consecration of the church and directed Fr. Maxim to commemorate the Chinese emperor and to begin preaching to the Chinese. Fr. Maxim reposed in 1712, thus ending his informal mission.

With Fr. Maxim’s passing, a formal Orthodox Mission was formed that acted as the official representative of the Russian government. The activities of the mission were subordinated to the Russian government diplomatic and political interests. This period lasted until 1860. During this period the composition and head of the mission changed about every ten years and was generally composed of four clergy and six laymen. The laymen were usually students whose duty was to learn the Chinese and Manchu languages and then became interpreters and eventually consuls for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The mission was financed by, and received direction from the government. This situation directly affected the missionary activities of the clergy. As the relations between Russia and China were defined formally, the work of each member of the mission was clearly defined. Under such circumstances, the missionary efforts of the Mission were greatly hindered and the number of conversions, evident in the small number of baptisms, was not significant.

Each change of the head of the mission has been identified serially. During the period to 1860 the number of changes was thirteen. Beijing being on the end of a long caravan route, communications with Russia were infrequent, only two to four times each year. This hampered the receipt of funds for the operation of the Mission.

Although hampered as missionaries by the political limitations, the succession of archimandrites and bishops who headed the Mission successfully introduced the cultural, ethnographical, and statistical information to Europeans through translations of Chinese literature. Among these works were the translations and compositions of Fr. Ioakinf (Bichurin) and a Chinese dictionary by Fr. Daniel Siviloff. During this 150 year period the Russian Orthodox Mission was confined to the mission center in Beijing. This confinement resulted in less than two hundred conversions of Chinese which included many who were descendants of the Albasin prisoners.

The Treaty of Tianjin (Tientsin) in 1858 changed the situation of the Beijing mission radically. The treaty admitted to China representatives of foreign governments and rights of residence in China to Christian missionaries. In the new period diplomatic and religious activities of the Beijing Mission were separated. Translations of the Scriptures began to appear. The Mission head, Archimandrite Gury (Karpov), participated actively in the negotiations of the Beijing Treaty of 1860 under which Russia gained lands along the Amur River. Having studied Chinese for many years he was active also in translating the New Testament into Chinese, as well as collecting earlier translations of Orthodox books for re-translation into the Chinese spoken language. He expanded preaching and lecturing in church, reaching areas beyond Beijing.

While the literary and translation efforts continued through most of the later part of the nineteenth century, the missionary work in the later part of the century lagged due to inadequate funding for preaching outside of Beijing, as well as the arrival of new missionaries whose Chinese language skills were inadequate. The era of an all-Russian clergy ended when a Chinese priest, Fr. Mitrophan Ji, was ordained in Japan by Bp. Nicholas of Tokyo on June 29, 1882. Fr. Mitrophan died a martyr in the June 11, 1900 Boxer uprising in China. The nearly 500 baptisms that had been performed by the Mission and the establishment of two new churches, one each in Hankou and Kalgan (Zhangjiakou) had not contributed significantly to the Mission’s missionary efforts.

With the arrival of Archimandrite Innocent in March 1897 the situation changed abruptly. Fr. Innocent immediately undertook reforms in the Mission: he established a monastery, instituted daily services in Chinese, established support for Albasins with business abilities, organized parish activities, dispatched preachers to the hither lands outside Beijing to spread the Gospel, and established charity efforts among the local poor. While Fr. Innocent’s arrival began a period of active missionary efforts, the beginning of the twentieth century also brought serious troubles for the Russian Orthodox Mission, as it did for other Christian missions. The Boxer (Yihetuan Movement) revolt in 1900 resulted in the destruction of the buildings in Beijing, Dongdingan, and Kalgan (Zhangjiakou). The riots caused the death of more than 200 Orthodox faithful. The losses also included the extensive library in the Beijing compound begun by Archimandrite Peter during the tenth mission. The Mission survived, and by 1902 there were 32 churches in China with nearly 6,000 members

Rising out of the ruins of the Boxer revolt, a new Mission attitude was established through the efforts of Fr. Innocent and with the support of the Holy Synod in Russia. Having been recalled to St. Petersburg for consultations concerning the mission, Fr. Innocent was consecrated bishop and returned to Beijing as Bishop of Beijing in August 1902, with jurisdiction over all the churches along the Chinese-Eastern Railway.

Rebuilding the mission began immediately, funded by the Chinese government as compensation for the damages caused by the Boxer Revolt. Additionally, nearly all of China was opened to missionary work. New churches and chapels began to appear. A church and school were opened in Yongpingfu in Zhili province. Also in Zhili province some twenty chapels were opened by a Chinese priest. In Weihuifu, a church and school were founded through the gratitude of a Henan province official who had received protection from Russians during the revolt.

By 1916, the Russian Orthodox Mission in China had grown greatly. In Beijing, three monasteries were established: Dormition Monastery, the Hermitage of the Exaltation of the Cross in Xishan (Western Hills near Beijing), and a women’s monastery. There were nineteen churches including four in Beijing and 32 missions including 14 in Zhili province, 12 in Hebei, four in Henan, one in Xi’anfu, and one in Mongolia. The Mission also controlled 17 schools for boys and three for girls. In addition the Mission maintained a number of institutions relating to the publication of books, and various work shops.

Evangelization of Chinese increased, and by 1916 the number of baptized Chinese numbered 5,587, including 583 who were baptized in 1915. The vast majority of teachers in the Mission schools were Chinese.

Following the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917, the Mission lost its support base and had to fend for itself. At the same time the arrival of many Russian refuges in China greatly increased the number of Orthodox believers. The number of churches also increased, largely to support the Russian arrivals. This led to the establishment of new dioceses. In China, dioceses were established around the cities of Shanghai and Tianjin, in addition to Beijing. A diocese in Harbin had developed out of support for the Russian colony associated with the Eastern China Railway.

During the years after the Bolshevik Revolution many of the Orthodox bishops joined with the exile Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, that was initially headquartered in Karlovci, Yugoslavia, but later in Munich, Germany and then New York in the United States. At the end of World War II, and with the arrival of Soviet forces, particularly in Manchuria, the Moscow Patriarchate gained jurisdiction over the Russian bishops in China and Harbin.

In 1949, after establishment of the People’s Republic of China that was under the control of the Chinese Communist Party, treaties between the Soviet and Chinese governments led to transfer of jurisdiction of the Russian churches to the Chinese. While many of the Russian expatriates were arrested by the communists for return to the Soviet Union, many returned voluntarily. Other families and clergy escaped to the non-communist world, many under the leadership of Bishop John of Shanghai.

In 1956, in fulfillment of agreements between the Soviet Union and Communist China, the Moscow Patriarchate granted autonomy to the Church of China formally ending the Russian Mission in China. At that time the Church of China had two Chinese bishops, a number of priests, and an estimated 20,000 faithful. Having remained under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate, Abp. Victor of Beijing, the last Russian bishop in China and leader of the last Spiritual Mission departed for the Soviet Union in 1956, closing the three hundred year old Russian Orthodox Mission in China.

Currently, the site of the mission in the district of Dongzhimen (Eastern Straight Gate) of Beijing is occupied by the Embassy of Russia.

Heads of mission

Period of diplomatic representatives

- First mission (1716-1728). Archimandrite Ilarion (Lezhaisky) Reposed in Beijing in 1717.

- Second mission (1729-1735). Archimandrite Antony (Platkovsky).

- Third mission (1736-1745). Archimandrite Illarion (Trusov). Reposed in Beijing in 1741.

- Fourth mission (1745-1755). Archimandrite Gervasy (Lintsevsky).

- Fifth mission (1755-1771). Archimandrite Amvrosy (Yumatov). Reposed in Beijing in 1771.

- Sixth mission (1771-1781). Archimandrite Nikolai (Tsvet).

- Seventh mission (1781-1794). Archimandrite Ioakim (Shishkovsky).

- Eighth mission (1794-1807). Archimandrite Sofrony (Gribovsky).

- Ninth mission (1807-1821). Archimandrite Iakinf (Bichurin). Reposed in 1853.

- Tenth mission (1821-1830). Archimandrite Peter (Kamensky). Reposed in 1845.

- Eleventh mission (1830-1840). Hieromonk (later Archimandrite) Veniamin (Morachevich).

- Twelfth mission (1840-1849). Archimandrite Policarp (Tugarinov).

- Thirteenth mission (1850-1858). Archimandrite Pallady (Kafarov). Also led the fifteenth mission.

Period of limited missionary activities

- Fourteenth mission (1858-1864). Archimandrite Gury (Karpov). In 1866, consecrated vicar Bishop of Cheboksary, Kazan Eparchy; In 1867, Bishop of Tauria and Simferopol; 1881, Archbishop; Reposed in 1882.

- Fifteenth mission (1865-1878). Archimandrite Pallady (Kafarov). Reposed in 1878 in Marseilles during return to Russia due to illness.

- Sixteenth mission (1879-1883). Archimandrite Flavian (Gorodetsky). In 1885, consecrated vicar bishop in the Don Diocese; In 1892, elevated to archbishop when ruler of the Diocese of Kholmsky and Warsaw; In 1903, elected Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia; Reposed in 1915.

- Seventeenth mission (1884-1896). Archimandrite Amfilohy (Lutovinov).

Period of active mission

- Eighteenth mission (1896-1931). Archimandrite Innocent (Figurovsky). In 1902 - elevated to the rank of Bishop of Pereyaslav, vicar of the Vladimir Eparchy; later elevated to Metropolitan of Beijing and China; Reposed in Beijing in 1931.

- Nineteenth mission (1931-1933). Archbishop Simon (Vinogradov); In 1919, consecrated Bishop of Shanghai; Reposed in Beijing in 1933.

- Twentieth mission (1933-1956). Bishop Victor (Svyatin). In 1932 consecrated Bishop of Shanghai; In 1938 he was elevated to the rank of archbishop and to Metropolitan in 1961. Reposed September 18, 1966.

See also

External links

- w:Albazinians

- Orthodoxy in China

- Russian Mission in China 1685-1745

- Russian Mission in China 1745-1755

Further Reading

- Eric Widmer. The Russian ecclesiastical mission in Peking during the eighteenth century. Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1976. 262 pp.

- (ISBN 0674781295; ISBN 9780674781290)