Difference between revisions of "Western Rite"

m (→France) |

(→Criticism: small expansion) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

| − | The Western Rite in the Orthodox Church is not without its critics. Some argue essentially that there is no liturgical tradition that can be viable within the Church other than the Byzantine ritual tradition, but that argument's main problem is its ignorance of the wide liturgical variety characteristic of the first millennium of the Church's history. | + | The Western Rite in the Orthodox Church is not without its critics. Some argue essentially that there is no liturgical tradition that can be viable within the Church other than the Byzantine ritual tradition, but that argument's main problem is its ignorance of the wide liturgical variety characteristic of the first millennium of the Church's history. For instance, many Orthodox Christians will boast of the Church's liturgical homogeneity, saying that no matter where one might go in the Orthodox world, the liturgy will be familiar, even if it's in another language. Yet those who find comfort in that claim might be surprised to learn that their first millennium counterparts would have been incapable of making such a claim—even if only the Eastern liturgical tradition were taken into account. |

| − | The more historically minded criticisms usually center around the idea that it is untenable to try to revive a liturgical tradition which was lost centuries ago when the West fell away from the [[Orthodox Church]]. This argument essentially states that, because the Western Rite died out in the Church, and because a continuous living tradition is a necessary element of liturgical practice, the Western Rite ought to be abandoned and only developments from the Byzantine Rite ought to be pursued. | + | The more historically minded criticisms of the Western Rite usually center around the idea that it is untenable to try to revive a liturgical tradition which was lost centuries ago when the West fell away from the [[Orthodox Church]]. This argument essentially states that, because the Western Rite died out in the Church, and because a continuous living tradition is a necessary element of liturgical practice, the Western Rite ought to be abandoned and only developments from the Byzantine Rite ought to be pursued. |

Proponents argue, however, that it is not a dogmatic principle of the Church that liturgical traditions can neither be revived nor created. After all, there are whole services even within the Byzantine Rite which are not universally practiced (e.g., the [[molieben]]), so they must have been invented somewhere along the way. Even then, the rites being used by Western Rite Orthodox Christians are not new, but mainly predate the [[Great Schism]]. | Proponents argue, however, that it is not a dogmatic principle of the Church that liturgical traditions can neither be revived nor created. After all, there are whole services even within the Byzantine Rite which are not universally practiced (e.g., the [[molieben]]), so they must have been invented somewhere along the way. Even then, the rites being used by Western Rite Orthodox Christians are not new, but mainly predate the [[Great Schism]]. | ||

Revision as of 01:25, March 2, 2005

The Western Rite is a strand of Orthodox Christian worship based on the liturgical traditions of the ancient pre-Schism Orthodox Church of the West. Western Rite Orthodox Christians hold in common the full Orthodox faith with their brethren of the Byzantine Rite, and most of the bishops who care for such parishes are themselves followers of the Byzantine Rite.

Contents

Modern History

The Nineteenth Century

In 1864, 44-year-old Joseph Julian Overbeck, a former German Catholic priest who had left the priesthood and later married, was chrismated into the Orthodox Church at the Russian Embassy Chapel in London. Overbeck was a Syriac scholar and professor in Bonn who had become disillusioned with the papal claims of supremacy. Two years after his chrismation, he published Catholic Orthodoxy and Anglo-Catholicism, in which he developed the schema with which he was about to begin his work for the next twenty years. In 1867, he published the first issue of the Orthodox Catholic Review, a periodical which "aimed at setting forth the truth of Catholic Orthodoxy as opposed to Popery and Protestantism, clearing its way through the heap of rubbish stored up by both parties for centuries past." Overbeck regarded both the Papacy and the Church of England to be on the verge of collapse.

In March of 1867, Overbeck circulated a petition to the Holy Synod of the Church of Russia explaining his designs and requesting the establishment of a Western Rite church in full communion with the Eastern Rite of the Orthodox Church, saying, "we are Westerns...and must plead an inalienable right to remain Westerns." In September of 1867 the petition, with some 122 signatures—mainly Tractarian clerics (the "Oxford Movement")—was sent to the Russian synod. Upon receipt, a synodal commission was formed, comprised of seven members under the Metropolitan of St. Petersburg, inviting Overbeck to attend the deliberations. Accompanying him was Fr. Eugene Popoff (chaplain of the Russian embassy in London), and the two were present in January of 1870 when the scheme was approved. Overbeck was then requested to submit a draft of the Western liturgy for examination.

The liturgy which Dr. Overbeck developed for the Russians was based on the 1570 Roman rite of Pope Pius V, but also included a brief epiclesis and the Trisagion hymn after the Gloria, "in remembrance of our union with the Orthodox Church." Returning to Russia in January of 1871, Overbeck submitted the rite. In two long sessions of the commission, the liturgy was examined and then approved for use.

Over the next few years, Overbeck mainly focused on the development of the Old Catholic movement in Europe (which had gone into schism from Rome over the new dogma of Papal Infallibility promulgated at the First Vatican Council), probably hoping to find fertile ground for the establishment of his liturgical use, a Western liturgical rite within the Orthodox Church. In his magazine, he engaged in polemics with both Roman Catholics and Anglicans, as well as Orthodox converts who used the Byzantine rite.

In 1876, he reiterated his design and issued an Appeal to the Patriarchs and Holy Synods of the Orthodox Catholic Church. Three years later, he travelled to Constantinople to meet the Ecumenical Patriarch, Ioachim III, who gave him authorization for delivering sermons and addresses in defense of Orthodoxy. In August of 1881, the Church of Constantinople appointed a commission to examine the scheme and made the announcement that "an agreement on certain points has already been reached," recognizing the right of the West to have a Western church and rite as had existed before the Great Schism.

Much to Overbeck's disappointment, no further developments occurred. He had hoped to be a priest within the Orthodox Church, but his marriage after his Roman Catholic ordination was seen as an impediment, rendering him ineligible. He became somewhat paranoid in his later years, especially regarding the Greeks in London as hostile toward him. The Orthodox Catholic Review ended its run in 1885, and seven years later he admitted that his project had failed, saying that he had had "Hopes entertained with joy by all the truly Orthodox, recommended and pushed forward by the Holy Synods of Russia, Romania and Serbia, approved by Patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria, Jerusalem, but finally crushed and destroyed by the veto of the Greek Synod!" He died in 1905, his dream unfulfilled.

Fr. Georges Florovsky wrote: "it was not just a fantastic dream. The question raised by Overbeck was pertinent, even if his own answer to it was confusedly conceived. And probably the vision of Overbeck was greater than his personal interpretation."

The Twentieth Century

In the twentieth century, two significant Western Rite Orthodox movements have occurred, building on the principles established by the work of Dr. Overbeck, one in France and the other in the United States.

France

In 1937, the Church of Russia received a small group under the former Liberal Catholic bishop, Louis-Charles (Irénée) Winnaert (1880-1937), dubbing them l'Eglise Orthodoxe Occidentale ("Western Orthodox Church"). The work of Winnaert was continued, though not without some occasional conflict, by Evgraph Kovalesky (1905-1970) and Lucien Chambault (later known as Pére Denis), the latter of which oversaw a small Orthodox Benedictine community in the rue d'Alleray in Paris. Also associated with them was the former Benedictine monk, Archimandrite Alexis van der Mensbrugghe (1899-1980), who favorably viewed the restoration of the ancient Roman rite cleansed of medieval accretions and supplemented by Gallican and Byzantine interpolations. In 1948, he published his Liturgie Orthodoxe de Rite Occidental and in 1962 the Missel Orthodoxe Rite Occidental.

After 1946, the Eglise Orthodoxe de France was developed by Kovalesky specifically with the intention to restore the ancient Gallican usage of the pre-Carolingian Roman rite, basing his work on the letters of St. Germanus, a 6th century bishop of Paris. During this troubled period, the Orthodox community in Paris went through several jurisdiction changes, but eventually Fr. Alexis returned to the Church of Russia and was consecrated to the episcopacy in 1960, continuing his Western Rite work under the auspices of the Moscow Patriarchate.

After some years of canonical limbo, Kovalesky's group came under the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia between 1959 and 1966, and Kovalesky himself was consecrated with the title of Bishop Jean de Saint-Denis in 1964. During this time, the Eglise Orthodoxe de France received considerable encouragement from St. John Maximovitch (who was ROCOR's representative in Western Europe at the time), and his death in 1966 was a serious blow to these French Orthodox Christians, who had had an influential and holy advocate in St. John.

Meanwhile, the Moscow Patriarchate's Western rite withered and came to an end, but Bishop Jean's church continued to thrive, though after St. John's death in 1966, they were again on canonical hiatus. Bishop Jean died in 1970, and then in 1972 the Church of Romania took the Eglise Orthodoxe de France under its omophorion. Gilles Bertrand-Hardy was consecrated as Bishop Germain de Saint-Denis, and the restored Gallican rite became the regular liturgy used in the many small French Orthodox parishes established throughout France. The full splendor of that liturgy can be seen in the Cathedral of St. Irénée in Boulevard Auguste-Blanqui in Paris. In 1994, after a lengthy conflict with the Romanian Holy Synod regarding various canonical irregularities, the Eglise again found itself in canonical limbo, where it remains to this day. The Romanian patriarchate established a deanery under Bishop Germain's brother Archpriest Gregoire to minister to those parishes which chose to stay with Romania.

In the late 1990s, negotiations had been underway with the Church of Serbia for the Eglise to come under its jurisdiction, but NATO's bombing of Kosovo in 1999 abruptly ended those hopes, as France was then seen by the Serbians as complicit in its persecution by the West.

The United States

In 1961, members of the Society of the Clerks of St. Basil (mainly centered in Mount Vernon, New York) were received into the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America by Metropolitan Antony (Bashir) of New York. The Society had been led up to that time by the uncanonical but widely respected Bishop Alexander Turner (née Paul Tyler Turner), who upon the reception of his group as the Western Rite Vicariate, became a canonical priest of the Orthodox Church and continued to guide the group as its Vicar-General. Fr. Alexander died in 1971, and the Western Rite Vicariate continued under the leadership of Fr. Paul W.S. Schneirla, who remains the Vicar-General to the present time.

Besides the original communities associated with the Society, a number of other parishes have been received into the Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Archdiocese, particularly as the theological and practical devolution of the Episcopal Church U.S.A. picked up speed in the latter half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. Additionally, several Western Rite missions have been founded, some growing into full parish status.

In 1995, the Church of Antioch also established a British Deanery to absorb converts from the Church of England, though not all of those parishes use the Western Rite, some following the Byzantine.

Elsewhere

Other small groups following the Western Rite have been received into the Orthodox Church, but usually have had little impact or sometimes declared their independence subsequent to their canonical reception. Western Rite parishes were established in Poland in 1926 when six parishes formerly of the Polish National Catholic Church (an Old Catholic communion) were received into the Orthodox Church, but that movement largely dwindled during World War II.

Further, the Oriental Orthodox have also done some Western Rite work. In 1889, the Syrian patriarchate of Antioch consecrated Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvarez as Archbishop of Ceylon, Goa and India, authorizing a Roman rite diocese under him. Additionally, in 1891, the Syrians consecrated Joseph René Vilatte as archbishop for the American Old Catholics.

Liturgy

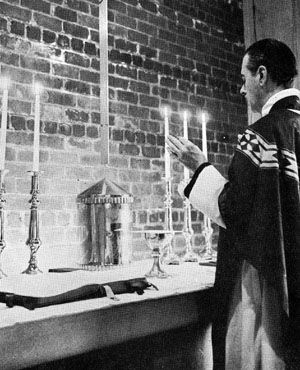

North American Western Rite parishes generally follow one (or sometimes both) of two types of traditional Western liturgical traditions. About 75% use the Liturgy of St. Tikhon of Moscow, which is an adaptation of the Communion service from the 1928 Anglican Book of Common Prayer and The Anglican Missal in the American Edition. The remaining 25% use the Liturgy of St. Gregory the Great, which is a modified form of the Tridentine Mass known to Roman Catholics before the liturgical reforms of Vatican II in the 1960s. The complete Roman rite of Benediction is also authorized.

The liturgy has much less repetition than its corresponding elements in the Byzantine rite, and generally has a more rational, succint manner to it. Celebrants wear distinctive Western vestments, and the faithful follow pious devotional customs particular to their tradition, as well.

Congregations

By far the largest group of these parishes in North America is represented by the Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America. The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) also has a small number of Western Rite parishes in addition to at least two monasteries, one located in Australia and another in Rhode Island which follows Benedictine liturgical traditions.

The abbot who led this latter monastery, named Christminster (or Christ the Savior Monastery), into communion with ROCOR once remarked to St. John Maximovitch that it was difficult to promote Western Rite Orthodoxy, whereupon the saint replied: "Never, never, never let anyone tell you that, in order to be Orthodox, you must also be eastern. The West was Orthodox for a thousand years, and her venerable liturgy is far older than any of her heresies."[1]

The Orthodox Church of France—which is currently of ambiguous status with regard to world Orthodoxy, but at one time was cared for by St. John Maximovitch and later by the Church of Romania—also uses a Western Rite liturgy based on ancient Gallican liturgical materials.

The Holy Synod of Milan, an Old Calendarist group, has a few communities (including one monastery) in the United States which worship according to Western rites, including a restored Sarum Rite.

It should also be noted that there are a number of groups who follow various Western rites and may call themselves Orthodox but are not part of or in communion with the historic Orthodox Church.

Criticism

The Western Rite in the Orthodox Church is not without its critics. Some argue essentially that there is no liturgical tradition that can be viable within the Church other than the Byzantine ritual tradition, but that argument's main problem is its ignorance of the wide liturgical variety characteristic of the first millennium of the Church's history. For instance, many Orthodox Christians will boast of the Church's liturgical homogeneity, saying that no matter where one might go in the Orthodox world, the liturgy will be familiar, even if it's in another language. Yet those who find comfort in that claim might be surprised to learn that their first millennium counterparts would have been incapable of making such a claim—even if only the Eastern liturgical tradition were taken into account.

The more historically minded criticisms of the Western Rite usually center around the idea that it is untenable to try to revive a liturgical tradition which was lost centuries ago when the West fell away from the Orthodox Church. This argument essentially states that, because the Western Rite died out in the Church, and because a continuous living tradition is a necessary element of liturgical practice, the Western Rite ought to be abandoned and only developments from the Byzantine Rite ought to be pursued.

Proponents argue, however, that it is not a dogmatic principle of the Church that liturgical traditions can neither be revived nor created. After all, there are whole services even within the Byzantine Rite which are not universally practiced (e.g., the molieben), so they must have been invented somewhere along the way. Even then, the rites being used by Western Rite Orthodox Christians are not new, but mainly predate the Great Schism.

Another criticism is that the Western Rite is inherently divisive. Following different liturgical traditions than their neighboring Byzantine Rite Orthodox Christians, those using the Western Rite do not share liturgical unity with them and present an unfamiliar face to the majority of Orthodox Christians. Though divisive differences exist between the various uses of the Byzantine Rite itself, the Western Rite is much more different. Again, this argument is based on the relatively new notion of liturgical homogeneity.

Whether the Western Rite will survive in the Orthodox Church and be accepted by the majority who follow the Byzantine Rite remains yet to be seen. In the meantime, the Byzantine Rite bishops who oversee the Western Rite parishes continue to declare their Western flocks to be Orthodox Christians and regard them as fully in communion with the rest of the Church.

Some Byzantine Rite Orthodox Christians, however, do not recognize the Orthodoxy of those in the Western Rite (despite their being under the jurisdiction of Byzantine Rite bishops with whom they themselves are in communion), and will not share the Eucharist with them, declaring them to be "Roman Catholics," "schismatics," or "Uniates." As yet, there are no schisms within the episcopacy of the Orthodox Church regarding the issue of Western Rite parishes.

An Orthodox Unia?

The situation of Western Orthodox parishes has been compared by some with the analogous status of the autonomous Uniate churches under the Roman Catholic Church. For centuries, there have been hierarchical churches in full communion with and in subjection to the Vatican, but which the Pope allows to follow liturgical customs and rules like those of the Orthodox Church (e.g., they use Bzyantine Rite liturgies, they confirm newly baptized infants via chrismation, they have married priests, their churches have iconostases, etc.). Additionally, as the Uniates share a common dogmatic requirement with Latin Rite Catholics, the Western Rite Orthodox share the same faith as their Byzantine Rite brethren.

However, unlike the Uniates, Western Rite Orthodox congregations are not mainly the result of large-scale ecclesiastical political machinations and schism but rather of small-scale genuine conversion to Orthodoxy by individuals and congregations. In any event, the criticism of the Western Rite based on its similarity with the Uniates is mainly guilt by association by means of a superficial similarity of form. Because the ideas are analogous, the argument goes, they must therefore both be wrong developments. Yet the more firmly established criticisms of Uniatism usually have nothing to do with rite, but rather with issues of dogma, ecclesiology, and allegedly subversive missionary work.

See also

- Western Rite Vicariate

- Sarum Rite

- Gallican Rite

- Stowe Missal

- Liturgy of St. Tikhon of Moscow

- Liturgy of St. Gregory the Great

Sources

- Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity, pp. 364-365, 514-515

External links

- Western Orthodoxy

- The Unofficial Western Rite Orthodoxy Website

- Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

Liturgies

- Text of the Liturgy of Saint Gregory

- Text of the Liturgy of Saint Tikhon

- Text of the Sarum Rite Liturgy as corrected for use within ROCOR by His Eminence Archbishop Hilarion

Book

- Children of the Promise: An Introduction to Western Rite Orthodoxy, by Fr. Michael Keiser

Introduction and History

- An Introduction to Western Rite Orthodoxy: Interview with Fr. Paul Schneirla and Fr. Michael Keiser on Come Receive the Light (audio)

- A Short History of the Western Rite, by Benjamin Andersen: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9

- An Introduction to Western Rite Orthodoxy, An electronic version of the now out-of-print Conciliar Press booklet; edited by Fr. Michael Trigg, Ph.D.

- The Western Rite: Its Fascinating Past and Its Promising Future, by Fr. Alexander Turner

- On the Western Rite Edict of Metropolitan Anthony (Bashir), by Fr. David Abramstov, in addition to an excerpt from the report of Metropolitan Anthony (Bashir) to the 1958 Archdiocesan Convention

- Western Orthodox Christians: Who Are They?, from Christminster (Providence, Rhode Island), a Benedictine Monastery under ROCOR

- What is Western-Rite Orthodoxy?, by Fr. Patrick McCauley

- The Twain Meet, by Fr. Paul W.S. Schneirla

- Western Rite Orthodox in our midst: Ad Fontes!, by Dr. Alexander Roman

Apologias

- Comments on the Western Rite by Bishop Basil (Essey) of Wichita

- Lux Occidentalis The Orthodox Western Rite and the Liturgical Tradition of Western Orthodox Christianity, with reference to The Orthodox Missal, Saint Luke's Priory Press, Stanton, NJ, 1995 by the Rev'd John Charles Connely (PDF)

- Doctrinal Issues: Western Rite Orthodoxy, from the Diocesan News for Clergy and Laity (February 1995), Greek Orthodox Diocese of Denver

- Western Rite Orthodoxy: Its history, its validity, and its opportunity, by Annette Milkovich, including an interview with Fr. Paul W.S. Schneirla, constituting a rough Western Rite "FAQ"

- Occidentalis - A Weblog of Orthodox Catholic Christianity in the Western Rite tradition

Criticism

- The Western Rite, by Fr. Alexander Schmemann

- Notes and Comments on the "Western Rite", ibid.

- News: Bishop Anthony Issues Encyclical on "Western Rite"

- Correspondence on the Western Rite between Bishop Anthony (Gergiannakis) of San Francisco and Fr. Paul W.S. Schneirla

- Some Thoughts on the "Western Rite" In Orthodoxy, by Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia

- The Western Rite - Some Final Comments, by Fr. Steven Tsichlis

- On the Question of Western Orthodoxy, by Patriarch Sergius I (Stragorodsky) of Moscow in a letter to Vladimir Lossky

- The "Western Rite": Is It Right for the Orthodox?, by Fr. Michael Johnson