Antimension

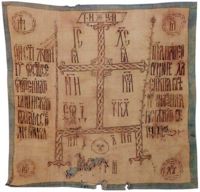

The antimension, (from the Greek: ἀντιμήνσιον, "instead of the table"; in Slavonic: antimins), is among the most important furnishings of the altar in Orthodox Christian liturgical traditions. It is a rectangular piece of cloth, of either linen or silk, typically decorated with representations of the entombment of Christ, the four Evangelists, and scriptural passages related to the Eucharist. A small relic of a martyr is sewn into it. The Eucharist cannot be celebrated without an antimension.

The antimension is placed in the center of the altar table and is unfolded only during the Divine Liturgy, before the Anaphora. At the end of the Liturgy, the antimension is folded in thirds, and then in thirds again, so that when it is unfolded the creases form a cross. When folded, the antimension sits in the center of another slightly larger cloth, the eileton (Slavonic: Ilitón) which is then folded around it in the same manner (3 x 3), encasing it completely. A flattened natural sponge is also kept inside the antimension, which is used to collect any crumbs which might fall onto the Holy Table. When the antimension and eiliton are folded, the Gospel Book is laid on top of them.

The antimension must be consecrated and signed by a bishop. The antimension and the chrism are the means by which a bishop indicates his permission for priests under his omophorion to celebrate the Divine Liturgy and Holy Mysteries in his absence, being in effect the church’s license to conduct divine services. If a bishop were to withdraw his permission to serve the Mysteries, he would do so by taking back the antimension and chrism from the priest. Whenever a bishop visits a church or monastery under his omophorion, he will enter the altar and inspect the antimension to be sure that it has been properly cared for, and that it is in fact the one that he issued.

Only a bishop, priest, or deacon is allowed to touch an antimension. Since the antimension is a consecrated object, they must be vested when they do so—the deacon should be fully vested, and the priest vested in at least stole (epitrachelion) and cuffs (epimanikia).

The antimension is a substitute for the altar table. A priest may celebrate the Eucharist on the antimension even if the altar table is not properly consecrated. In emergencies, when an altar table is not available, the antimension serves a very important pastoral need by enabling the use of unconsecrated tables for divine services outside of churches or chapels. Formerly if the priest celebrated at a consecrated altar, the sacred elements were placed only on the eileton. However, in current practice the priest always uses the antimension, even on a consecrated altar that has relics sealed in it.

At the Divine Liturgy, during the Litanies (Ektenias) that precede the Great Entrance the eiliton is opened fully and the antimension is opened three-quarters of the way, leaving the top portion folded. Then, during the Litany of the Catechumens, when the deacon says, "That He (God) may reveal unto them (the catechumens) the Gospel of righteousness," the priest unfolds the last portion of the antimension, revealing the mystery of Christ's death and resurrection. After the Entrance, the chalice and diskos are placed on the antimension and the Gifts (bread and wine) are consecrated. The antimension remains unfolded until after all have received Holy Communion and the chalice and diskos are returned to the Table of oblation (Prothesis). The deacon (or, if there is no deacon, the priest) must very carefully inspect the antimension to be sure there are no crumbs left on it. Then, it is folded, followed by folding the eiliton, and after which the Gospel Book placed on top of it.

Although St. Theodore the Studite (759-826) mentions "fabric altars," the term "antimension" is not found before the late twelfth century.

Oriental Orthodox practice

In churches of the Syriac tradition a wooden tablet, the ţablîtho, is the liturgical equivalent of the antimension. However, it is no longer used by the Antiochian Orthodox Church which follows the liturgical practice of Constantinople, and thus uses the antimension.

In the Ethiopian Tawahedo Church, the tâbot is functionally similar to the tablitho. However, this word is also used in the Ge'ez language to describe the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark is symbolically represented by the manbara tâbôt (throne of the Ark), a casket that sits on the altar table. The tabot itself, the wooden tablet, is taken out before the anaphora, and symbolizes the giving of the Ten Commandments.

Source

External links

- Antimens or Antiminsion from A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology by Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D. (Orthodox Research Institute)

- Antimensions from Mount Athos at the Orthodox Multimedia Gallery

- The Antimension