John Paul I

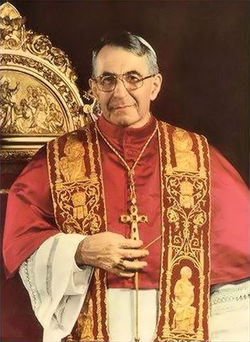

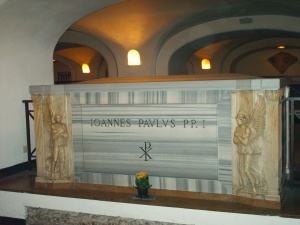

Pope John Paul I ((Latin)

- Ioannes Paulus PP. I, (Italian)

- Giovanni Paolo I), born Albino Luciani (17 October 1912 – September 28 1978), reigned as the 263rd Pope of the Roman Catholic Church and as Sovereign of Vatican City from August 26, 1978 until his death 33 days later. His sudden and mysterious death, the result of an apparent heart attack, has led to rumours of foul play that have periodically resurfaced.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] Pope John Paul I's charismatic reign is among the shortest in papal history, resulting in the most recent Year of Three Popes. He was also the first Pope to be born in the 20th century and the last Pope to die in it.

John Paul I was the first pope since Pius X (reigned 1903–14) to have a pastoral[10] rather than a diplomatic or scholarly background.[1] In Italy he is remembered with the appellatives of "Il Papa del Sorriso" (The Smiling Pope)[11] and "Il Sorriso di Dio" (The smile of God).[12] Time magazine and other publications referred to him as The September Pope.[13]

Contents

Biography

Early Years

Albino Luciani was born on October 17, 1912 in Forno di Canale (now Canale d'Agordo) in Belluno, a province of the Veneto region in Northern Italy. He was the son of Giovanni Luciani (1872?–1952), a bricklayer, and Bortola Tancon (1879?–1948). Albino was followed by two brothers, Federico (1915–1916) and Edoardo (1917–2008), and a sister, Antonia (1920–2009).

Luciani entered the minor seminary of Feltre in 1923, where his teachers found him "too lively", and later went on to the major seminary of Belluno. During his stay at Belluno, he attempted to join the Jesuits, but was denied by the seminary's rector, Bishop Giosuè Cattarossi.[note 1]

Ordained a priest on July 7, 1935, Luciani then served as a curate in his native Forno de Canale before becoming a professor and the vice-rector of the Belluno seminary in 1937. Among the different subjects, he taught dogmatic and moral theology, Canon law and sacred art.

In 1941, Luciani began to seek a doctorate in theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University, which required at least one year's attendance in Rome. However, the seminary's superiors wanted him to continue teaching during his doctoral studies; the situation was resolved by a special dispensation of Pope Pius XII himself, on March 27, 1941. His thesis (The origin of the human soul according to Antonio Rosmini) largely attacked Rosmini's theology, and earned him his doctorate magna cum laude.

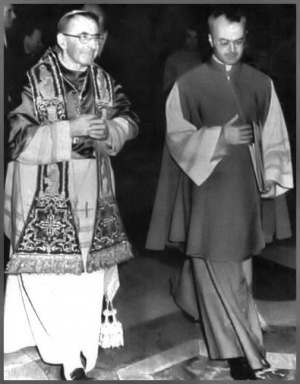

.In 1947, he was named vicar general to Bishop Girolamo Bortignon, OFM Cap, of Belluno. Two years later, in 1949, he was placed in charge of diocesan catechetics.On December 15, 1958, Luciani was appointed Bishop of Vittorio Veneto by Pope John XXIII. He received his episcopal consecration on the following December 27, from Pope John himself, with Bishops Bortignon and Gioacchino Muccin serving as co-consecrators. As a bishop, he participated in all the sessions of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965).

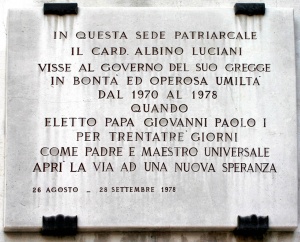

On December 15, 1969, he was appointed Patriarch of Venice by Pope Paul VI and took possession of the Archdiocese on February 3, 1970.

Pope Paul created Luciani Cardinal-Priest of San Marco, Rome in the consistory on March 5, 1973. On becoming a Cardinal, he said: "History is history. We must look to the future with fresh hopes and ideas."[14] Catholics were struck by his humility, a prime example being his embarrassment when Paul VI once removed his papal stole and put it on Patriarch Luciani. He recalls the occasion in his first Angelus thus:[15]

Pope Paul VI made me blush to the roots of my hair in the presence of 20,000 people, because he removed his stole and placed it on my shoulders. Never have I blushed so much!

Papacy

Election

Luciani was elected on the fourth ballot of the August 1978 papal conclave. Senior Cardinal Deacon Pericle Felici announced that the Cardinals had elected Venice patriarch Albino Luciani to be Pope John Paul I.[16] He chose the regnal name of John Paul, the first double name in the history of the papacy, explaining in his Angelus that he took it as a thankful honour to his two immediate predecessors: John XXIII, who had named him a bishop, and Paul VI, who had named him Patriarch of Venice and a cardinal.[17] He was also the first (and so far only) pope to use "the first" in his regnal name.[18][note 2]

"The choice of the name,...indicates he will work for the continued aggiornamento - renewal - of the church, as Pope John set it into motion, but, like Pope Paul, will not allow either worldly pressures or the humanists within the church to allow that change to become disorderly."[19]

Observers have suggested that his selection was linked to the rumoured divisions between rival camps within the College of Cardinals:[17]

- Conservatives and Curialists supporting Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, who favoured a more conservative interpretation or even correction of Vatican II's reforms. There remains a conspiracy theory (the so-called 'Siri Conspiracy') concerning allegations Siri was actually elected in this conclave, but then forced to withdraw acceptance of his election.

- Those who favoured a more liberal interpretation of Vatican II's reforms, and some Italian cardinals supporting Cardinal Giovanni Benelli, who was opposed because of his "autocratic" tendencies.

Outside the Italians, who were experiencing diminished influence within the increasingly internationalist College of Cardinals, were figures like Cardinal Karol Wojtyła,[17] and Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger.

Over the days following the conclave, cardinals effectively declared that with general great joy they had elected "God's candidate".[17] Argentine Cardinal Eduardo Francisco Pironio stated that, "We were witnesses of a moral miracle."[17] English Cardinal Basil Hume commented that "Seldom have I had such an experience of the presence of God...I am not one for whom the dictates of the Holy Spirit are self-evident. I'm slightly hard-boiled on that...But for me he was God's candidate."[2] And later, Mother Teresa commented: "He has been the greatest gift of God, a sunray of God's love shining in the darkness of the world."[17]

Russian Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) of Leningrad, who was present at his installation, collapsed and died during the ceremony, and the new Pope prayed over him.[20]

Church Policies

Humanising the papacy

After his election, John Paul quickly made several decisions that would "humanise" the office of pope, admitting publicly he had turned scarlet when Paul VI had named him the Patriarch of Venice. He was the first modern pope to speak in the singular form, using 'I' instead of the royal we, though the official records of his speeches were often rewritten in more formal style by traditionalist aides, who reinstated the royal we in press releases and in L'Osservatore Romano. He was the first to refuse the sedia gestatoria, until Vatican pressure convinced him of its need, in order to allow the faithful to see him.

He was the first pope to choose an "investiture" to commence his papacy rather than the traditional papal coronation.

One of his remarks, reported in the press, was that God "is our father; even more he is our mother,"[21][22] referring to Isaiah 49:14–15, which compares God to a mother who will never forget her child Zion. The comment appeared in his September 10 Angelus address, which urged prayer for the upcoming Camp David Accords.[21]

Encyclical on Devolution

John Paul I intended to prepare an encyclical in order to confirm the lines of the Second Vatican Council ("an extraordinary long-range historical event and of growth for the Church," he said) and to enforce the Church's discipline in the life of priests and the faithful. In discipline, he was a reformist, instead, and was the author of initiatives such as the devolution[note 3] of one per cent of each church's entries for the poor churches in the Third World.

The visit of Jorge Rafael Videla, president of the Argentine junta, to the Vatican caused considerable controversy, especially when the Pope reminded Videla about human rights violations taking place in Argentina during the so-called Dirty War.

Moral theology

The moral theology of John Paul I has been openly debated due to his interpretation of Humanae Vitae.[note 4] According to journalist John L. Allen "John Paul I would not have insisted upon the negative judgment in Humanae Vitae as aggressively and publicly as John Paul II, and probably would not have treated it as a quasi-infallible teaching."[23][24]

However, others have argued, "Luciani was intransigent with his upholding of the teaching of the Church and severe with those, who through intellectual pride and disobedience paid no attention to the Church's prohibition of contraception", though while not condoning the sin, he was tolerant of those who sincerely tried and failed to live up to the Church's teaching."[11]

Personality

John Paul was regarded as a skilled communicator and writer, and has left behind some writings. His book Illustrissimi, written while he was a Cardinal, is a series of letters to a wide collection of historical and fictional persons. Among those still available are his letters to Jesus,[25] King David,[26] Figaro the Barber,[27] Empress Maria Theresa[28] and Pinocchio.[29] Others 'written to' included Mark Twain, Charles Dickens and Christopher Marlowe.

John Paul impressed people with his personal warmth. There are reports that within the Vatican he was seen as an intellectual lightweight not up to the responsibilities of the papacy, although British author David Yallop ("In God's Name") says that this is the result of a whispering campaign by people in the Vatican who were opposed to Luciani's policies. In the words of English journalist and author John Cornwell, "they treated him with condescension"; one senior cleric discussing Luciani said "they have elected Peter Sellers."[30] Critics contrasted his sermons mentioning Pinocchio to the learned intellectual discourses of Pius XII or Paul VI. Visitors spoke of his isolation and loneliness, and the fact that he was the first pope in decades not to have had either a diplomatic role (like Pius XI and John XXIII) or Curial role (like Pius XII and Paul VI) in the Church.

His personal impact, however, was twofold: his image as a warm, gentle, kind man captivated the world. This image was immediately formed when he was presented to the crowd in St. Peter's Square following his election. The warmth of his presence made him a much-loved figure before he even spoke a word. The media in particular fell under his spell. He was a skilled orator. Whereas Pope Paul VI spoke as if delivering a doctoral thesis, John Paul I produced warmth, laughter, a 'feel-good factor,' and plenty of media-friendly sound bites.

According to his aides, he was not the naive idealist his critics made him out to be. Cardinal Giuseppe Caprio, the substitute Papal Secretary of State, said that John Paul quickly accepted his new role and performed it with confidence.[note 5]

John Paul was the first pope to admit that the prospect of the papacy had daunted him to the point that other cardinals had to encourage him to accept it. He refused to have the millennium-old traditional Papal Coronation and wear the Papal Tiara.[31] He instead chose to have a simplified Papal Inauguration Mass. John Paul I used as his motto Humilitas. In his notable Angelus of August 27, 1978 (delivered on the first full day of his papacy) he impressed the world with his natural friendliness.[15]

Death

John Paul I was found dead sitting up in his bed shortly before dawn on September 29, 1978,[32] just 33 days into his papacy. The Vatican reported that the 65-year-old pope most likely died the previous night of a heart attack:

"The official version of Pope John Paul's death is that the pontiff, who would have been 66 years old on Oct. 17, succumbed to a 'massive' cardiac infarction, or heart attack, presumably around 11 p.m. on Sept. 29."[8]

It has been claimed that the Vatican altered some of the details of the discovery of the death to avoid possible unseemliness[9][33] in that he was discovered by Sister Vincenza, a nun.[34]

As it is not the custom with the death of a pope, an autopsy was not performed. Yet this, along with inconsistent statements made following the Pope's death, led to a number of conspiracy theories concerning it. These statements relate to who found the Pope's body, the time when he was found, and what papers were in his hand. The Vatican has yet to investigate any of these claims.

At the pope's funeral Mass in 1978 Cardinal Carlo Confalonieri aptly observed: "He passed as a meteor which unexpectedly lights up the heavens and then disappears, leaving us amazed and astonished." [35]

Legacy

Pope John Paul I was the first pope to abandon the Papal Coronation, and he was the first Pope to choose a double name (John Paul) for his papal name. His successor, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, chose the same name. As pope, Luciani quickly discarded the royal "we" and disdained the sedia gestatoria, the portable throne in which popes are hoisted onto the shoulders of their subjects and carried in majestic procession like conquering monarchs. This pope's unexpected greeting to those who met with him at the Vatican was, "How can I serve you?"[35]

In just a month Pope John Paul I captured the hearts of people worldwide, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, who witnessed in him the welcome but unexpected triumph of humility.[35] Luciani picked "Humilitas" as his episcopal motto, an appropriate choice for a prince of the church who regard-ed himself as "poor dust." "We must feel small before God," he preached; and he lived that conviction faithfully, often describing himself publicly as "a poor man accustomed to small things and silence."[35]

According to Luciani biographer Loris Serafini, the dedication of a museum and library in the pope's honor will coincide with the centenary celebration of his birth on October 17, 2012.[35]

Initiation of His Canonisation Process

The process of canonisation formally began in 1990 with the petition by 226 Brazilian bishops, including four cardinals.

On August 26, 2002, Bishop Vincenzo Savio announced the start of the preliminary phase to collect documents and testimonies necessary to start the process of canonisation. On June 8, 2003 the Congregation for the Causes of Saints gave its assent to the work. On November 23, the process formally opened in the Cathedral Basilica of Belluno with Cardinal José Saraiva Martins in charge.[36][37] The Diocesan inquiry subsequently concluded on November 11, 2006 at Belluno, without finding evidence of a miracle.[38]

In June 2009, the Vatican began the "Roman" phase of the beatification process for John Paul I, drawing upon the testimony of Giuseppe Denora di Altamura who claimed to have been cured of lymphoma cancer 14 years earlier through the intercession of the late pope.[38] An official investigation into the alleged miracle is now under way.[39]

For Luciani to be beatified, the investigators have to certify at least one miracle. For canonisation there must be a second miracle, though the reigning pope may waive these requirements altogether, as is often done in the case of beatified popes.[40]

As Author

- Pope John Paul I. Illustrissimi: The Letters of Pope John Paul I. Transl.: Isabel Quigly. Reprinted: Gracewing Publishing, 2001. 290 pp. ISBN 9780852445495

- Pope John Paul I. Pope John Paul I. United States Catholic Conference, 1979. 27 pp. (Text of six separate addresses of Pope John Paul I)

- John Paul I on EWTN. Speech on "Church Discipline, Evangelization, Ecumenism, Peace." L'Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition in English, 31 August 1978, page 6.

In the Media

- Americian singer-songwriter Patti Smith's recitative song "Wave" is about Luciani, and her 1979 Wave album is dedicated to him.

- In 1984 David Yallop's book In God's Name developed the theories behind the alleged murder of John Paul I.

- In 1986 the play Hey, Luciani, which was written by Mark E. Smith, best known as the lead singer of the English band The Fall, ran for two weeks at Riverside Studios, Hammersmith, west London. In the same month The Fall released one of the songs from the play, "Hey! Luciani," as a single.

- In 1989 John Cornwell's book A Thief in the Night (Cornwell book) challenged previous writings on the subject by David Yallop.

- The 1990 film The Godfather Part III included the assassination theory of Pope John Paul I, although the character's lay name differs from the actual Pope's.

- Robert Littell's 2002 book The Company portrays John Paul I's death as a KGB-directed assassination.

- In 2006, the Italian Public Broadcasting Service, RAI, produced a television miniseries about the life of John Paul I, called Papa Luciani: Il sorriso di Dio (literally, "Pope Luciani: The smile of God"). It stars Italian comedian Neri Marcorè in the titular role.

- Portuguese author Luis Miguel Rocha's 2008 fiction book The Last Pope claims that John Paul I was assassinated.

- On 11 October 2008, BBC Radio 4 broadcast Conclave by Hugh Costello as part of the Saturday Play series, starring David Calder as Cardinal Franz Koenig, Allison Reid as Hannah Popper, Nicholas Le Prevost as Cardinal Giovanni Benelli and Andrew Hilton as Cardinal Karol Wojtyla (the future John Paul II). The play takes place after John Paul I's mysterious death, with the election of a new Pope taking place in an atmosphere of high tension between opposing factions within the Vatican (including those who want to elect the first non-Italian Pope for over four hundred years). The production was re-broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on February 25, 2011 as part of the Friday Play series.

See also

Wikipedia

- Papal conclave, August 1978

- Moral theology of John Paul I

- Pope John Paul I conspiracy theories

- In God's Name. (A 1984 book by British author David Yallop about Pope John Paul I's death)

- A Thief in the Night. (A 1989 book by British historian and journalist John Cornwell, in which the author challenges previous writings on the subject by David Yallop)

| John Paul I

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Giovanni Urbani |

Patriarch of Venice 1970–1978 |

Succeeded by: Marco Cé |

| Preceded by: Paul VI of Rome |

Roman Catholic Pope 26 August 1978 - 28 September 1978 |

Succeeded by: John Paul II |

Further Reading

Books

- Peter Hebblethwaite. The Year of Three Popes. Collins, 1978. 229 pp. ISBN 9780002150477

- David Yallop. In God's Name: An Investigation Into the Murder of Pope John Paul I. 1984. Reprint: Carroll & Graf, 2007. 480 pp. ISBN 9780786719846

- John Cornwell. A Thief in the Night: Life and Death in the Vatican. 1989. Reprint: Penguin Books, 2001. 366 pp. ISBN 9780141001838

- Raymond Seabeck and Lauretta Seabeck. The Smiling Pope: The Life And Teaching Of John Paul I Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, 2004. 253 pp. ISBN 9781931709972

- George Lucien Gregoire. Murder in the Vatican. AuthorHouse, 2008. 404 pp. ISBN 9781434387226

- (Italian)

Loris Serafini. Albino Luciani. Il papa del sorriso. (Albino Luciani. The Smiling Pope) 3rd Edition. EMP, 2008. 192 pp. ISBN 9788825021035

- (Spanish)

Fr. Jesús López Sáez. Juan Pablo I: Caso Abierto (John Paul I: Cold Case). Sepha, 2010. 382 pp. ISBN 9788496764934

- (Spanish)

Fr. Jesús López Sáez. Se Pedirá Cuenta: Muerte Y Figura De Juan Pablo I (Colección Tratados de testimonio). 3rd Edition. Orígenes, 1991. 175 pp. ISBN 9788478250462

Books In Fiction

- (French)

Vladimir Volkoff. L'hôte du Pape: Roman (The Pope’s Guest). Rocher, 2004. 334 pp. ISBN 9782268049328

- Luís Miguel Rocha. The Last Pope. Penguin, 2009. 419 pp. ISBN 9780515146608

Articles

- Mo Guernon. "The Forgotten Pope: Why Albino Luciani's Holiness Should be Celebrated." America. 205.12 (Oct. 24, 2011): pp.19+.

- John Julius Norwich. "WAS POPE JOHN PAUL I MURDERED? A sealed bed chamber. An archbishop with links to the Mafia. An embalming carried out with indecent - improper - haste... And one leading historian's burning question:." Mail on Sunday [London, England] 8 May 2011: 26.

- "The Roman Catholic Church will investigate a life-saving miracle attributed to the late Pope John Paul I, bringing the pontiff who served only 33 days in 1978 one step closer to possible sainthood." The Christian Century 124.8 (Apr. 17, 2007): p15.

- Levi Fernandes. "Pope John Paul I assassinated over reform plans, author charges." Agence France Presse -- English. December 18, 2005 Sunday 4:38 AM GMT.

- "Belluno Bishop Says John Paul I Died From Stroke." ANSA English Media Service. January 2, 2004.

- Tom Newton Dunn. "Was Murder Committed in the Vatican? Cardinal Aloisio Lorscheider Talks of Doubts Over the Death of Pope John Paul I." The Mirror. August 28, 1998, Friday. pg.8.

- Eugene Kennedy (Professor of Psychology at Loyola University). "Was The Pope Murdered?" The New York Times. November 5, 1989, Sunday, Late Edition - Final. Section 7; Page 15, Column 1; Book Review Desk.

- "Vatican still owes us an up-front accounting of role in bank collapse." The Toronto Star (Saturday Second Edition). August 8, 1987. Pg. M13.

- "Vatican Rejects Poison Charge as 'Fanciful'." The Miami Herald. June 13, 1984 Wednesday.

- "Several Questions Unanswered in Pope's Death." The Globe and Mail. Sunday October 7, 1978.

- "Religion: How Pope John Paul I Won." TIME Sept. 11, 1978.

- "A Pastor for Pope." The Globe and Mail. Monday August 28, 1978.

- "Catholic Church Gets Champion of the Poor; Combination of Names Hints New Pope's Direction." The Globe and Mail. Monday August 28, 1978.

Notes

- ↑ Yallop, David (1985). In God's name: an investigation into the murder of Pope John Paul I. p.16, quotation:

So strongly did the writings of Couwase (Jean Pierre de Caussade) influence him that Luciani began to think seriously of becoming a Jesuit. He watched as first one, then a second, of his close friends went to the rector, Bishop Giouse Cattarossi, and asked for permission to join the Jesuit order. In both instances the permission was granted. Luciani went and asked for permission. The bishop considered the request, then responded, "No, three is one too many. You had better stay here."

- ↑ The last original name was Pope Landone in 913 A.D.

- ↑ Devolution is the statutory granting of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to government at a subnational level, such as a regional, local, or state level. Devolution can be mainly financial, e.g. giving areas a budget which was formerly administered by central government. However, the power to make legislation relevant to the area may also be granted.

- ↑ An encyclical written by Pope Paul VI and issued on July 25, 1968.

- ↑ "We must not be deceived by his smile. He listened, he asked for information, he studied. But once he made a decision, he did not go back on it, unless new facts came to light.... With absolute respect to persons, the Pope had no intentions of deviating from what had been the rule of his life and the direction of his pastoral action: fatherly, yes, but absolutely firm in the guidance of the souls entrusted by God to his care."

- Quoted in Raymond Seabeck. The Smiling Pope, The Life and Teaching of John Paul I. Our Sunday Visitor Press, 2004. p.65.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "John Paul I." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Julius Norwich. "WAS POPE JOHN PAUL I MURDERED? A sealed bed chamber. An archbishop with links to the Mafia. An embalming carried out with indecent - improper - haste... And one leading historian's burning question:." Mail on Sunday [London, England] 8 May 2011: 26.

- ↑ Levi Fernandes. "Pope John Paul I assassinated over reform plans, author charges." Agence France Presse -- English. December 18, 2005 Sunday 4:38 AM GMT.

- ↑ Tom Newton Dunn. "Was Murder Committed in the Vatican? Cardinal Aloisio Lorscheider Talks of Doubts Over the Death of Pope John Paul I." The Mirror. August 28, 1998, Friday. pg.8.

- ↑ Eugene Kennedy (Professor of psychology at Loyola University). "Was The Pope Murdered?" The New York Times. November 5, 1989, Sunday, Late Edition - Final. Section 7; Page 15, Column 1; Book Review Desk.

- ↑ "Vulnerability of Popes who 'Step in the Way of Secret Societies'." BBC Summary of World Broadcasts (Text of commentary). June 14, 1984, Thursday.

- ↑ "Vatican Rejects Poison Charge as 'Fanciful'." The Miami Herald. June 13, 1984 Wednesday.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Several Questions Unanswered in Pope's Death." The Globe and Mail. Sunday October 7, 1978.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Evidence of foul play in Pope death claimed". Chicago Tribune. 7 October 1978.

- ↑ "A Pastor for Pope." The Globe and Mail. Monday August 28, 1978.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Raymond and Lauretta. The Smiling Pope, The Life & Teaching of John Paul I. Our Sunday Visitor Press, 2004.

- ↑ Papa Luciani: Il sorriso di Dio (Pope Luciani: The Smile of God). Radiotelevisione Italia 2006 documentary.

- ↑ Time (Cover Story). The September Pope. Monday, 9 Oct 1978. Retrieved: 20 August 2012.

- ↑ "Glassworker's son surprise choice for Pope." The Globe and Mail (Reuters). September 30, 1978.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "FIRST ANGELUS ADDRESS, Pope John Paul I". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 27 August 1978. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ↑ UPI.com. 1978 Year in Review: The Election of Pope John Paul II. Retrieved: 2012-08-20.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Gloria C. Molinari. The Conclave: 25 – 26 August 1978. Retrieved: 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Yallop, David (1985). In God's name: an investigation into the murder of Pope John Paul I. p.75.

- ↑ "Catholic Church Gets Champion of the Poor; Combination of Names Hints New Pope's Direction." The Globe and Mail. Monday August 28, 1978.

- ↑ "Boris Georgyevich Rotov Nikodim". Crystal Reference Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Angelus Address". Vatican official website. 10 September 1978. Retrieved: May 20, 2012.

- ↑ Edward Magri. "Pontiff's Activities Summarized: Pope's Popularity Was Immediate." Sarasota Herald-Tribune (Google News). Sat. September 30, 1978. Pg.5-A. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ John L. Allen Jr. "The battle over "theology of pluralism"; Pope John Paul I and the pill; keeping an eye on the conclave; Archbishop Denis Hurley reminisces about Vatican II". National Catholic Reporter - The Word from Rome. September 5, 2003. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Kay Withers. "Pope John Paul I and Birth Control." America. March 24, 1979. pp.233–34.

- ↑ Albino Luciani. "Letters to Jesus Christ". Papaluciani.com (Gloria C. Molinari). May 1974. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Albino Luciani. "Letter: the Biblical King David". Papaluciani.com (Gloria C. Molinari). February 1972. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Albino Luciani. "Figaro the Barber". Papaluciani.com (Gloria C. Molinari). April 1972. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Albino Luciani. "Mary Theresa of Austria". Papaluciani.com (Gloria C. Molinari). July 1971. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Albino Luciani. "Pinocchio". Papaluciani.com (Gloria C. Molinari). June 1972. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Joseph McCabe. A History of the Popes. Excerpts from: A History of the Popes, Section Nine.

- ↑ Romano Pontifici Eligendo. Paul VI's Apostolic Constitution on the election on the pontiff - Section 92. 1975.

- ↑ NBC Radio News announces Pope John Paul I Death (In RealAudio).

- ↑ "BISHOP TELLS STORY OF POPE JOHN PAUL I'S DEATH HE DEBUNKS CONSPIRACY THEORY, BUTS SAYS VATICAN ALTERED SOME DETAILS". St. Louis Dispatch. 11 October 1998. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Foul Play Suspected in Pope's Death?". Baltimore Afro-American. 10 October 1978. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Mo Guernon. "The Forgotten Pope: Why Albino Luciani's Holiness Should be Celebrated." America. 205.12 (Oct. 24, 2011): pp.19+.

- ↑ (Italian) Congregation for the Causes of Saints. Solemn Opening of the Cause for Canonization of the Servant of God, Albino Luciani, Pope John Paul I. 23 November 2003. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ UPI.com John Paul I on Sainthood Track. United Press International, Nov 12, 2006. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "The Roman Catholic Church will investigate a life-saving miracle attributed to the late Pope John Paul I, bringing the pontiff who served only 33 days in 1978 one step closer to possible sainthood." The Christian Century 124.8 (Apr. 17, 2007): p15.

- ↑ Edward Pentin. John Paul I's Miracle Goes to Rome. National Catholic Register, June 08, 2009. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ↑ What Is a Saint? Catholic-Pages.com. JUL 29, 1997.

Sources

- Pope John Paul I. Wikipedia (Retrieved: August 20, 2012).

External Links

- The Holy See. John Paul I. (Vatican's website)

- SaintPetersBasilica.org. The Tomb of John Paul I - Vatican Grottoes.

- Fondazione Papa Luciani Giovanni Paolo I. (Website of the Foundation Papa Luciani - English).

- An interview with Dr John Magee, former private secretary to John Paul I, on the occasion of John Paul II's funeral is available here. From RTÉ Radio One's "News At One" on 8 April 2005.