Life

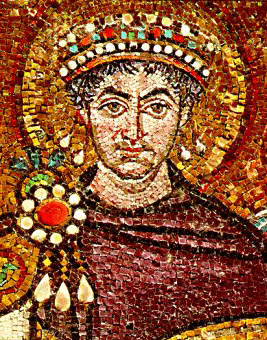

Justinian's full name was Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus. He is said to be of Slavic descent, probably born in a small village called Tauresium in Illyricum, near Scupi (present day Skopje, Macedonia), on May 11, 483, to Vigilantia. His mother Vigilantia was the sister of the highly esteemed General Justin, who rose from the ranks of the army to become emperor. His uncle adopted him and ensured the boy's education. Justinian was superbly well educated in jurisprudence, theology and Roman history. His military career featured rapid advancement, and a great future opened up for him when, in 518, Justin became emperor. Justinian was appointed consul in 521, and later as commander of the army of the east. He was functioning as virtual regent long before Justin made him associate emperor on April 1, 527.

Four months later, Justinian became the sole sovereign upon Justin I's death. His administration had world-wide impact, constituting a distinct epoch in the history of the Byzantine Empire and the Orthodox Church. He was a man of unusual capacity for work (sometimes called the "emperor who never sleeps") and possessed a temperate, affable, and lively character, but he was also unscrupulous and crafty when it served him. He was the last emperor to attempt to restore the Roman Empire to the territories it enjoyed under Theodosius I.

He surrounded himself with men and women of extraordinary talent, "new men" culled not from the aristocratic ranks, but appointed based on merit. In 523 he married Theodora, who was by profession a courtesan (or actress or circus performer, according which source one believes) about 20 years his junior. According to the historian Procopius, notorious for his slanderous dislike of the royal couple, Justinian is said to have met her at a show where she and a trained goose performed Leda and the Swan, a play that managed to mock Greek mythology and Christian morality at the same time. Justinian would have, in earlier times, been unable to marry her because of her class, but his uncle Emperor Justin I had passed a law allowing intermarriage between social classes. Theodora would become very influential in the politics of the empire, and later emperors would follow Justinian's precedent and marry outside of the aristocratic class. The marriage was a source of scandal, but Theodora would prove to be very intelligent, "street smart," a good judge of character, and Justinian's greatest supporter.

Theodora died in 548; Justinian outlived her for almost twenty years, dying on November 13 or 14, 565.

Legal and military accomplishments

Justinian achieved lasting influence for his judicial reforms, notably the summation of all Roman law, something that had never been done before. Justinian commissioned quaestor Tribonian to the task, and he issued the first draft of the Corpus Juris Civilis on April 7, 529, in three parts: Digesta (or Digest or Pandectae), Institutiones (or Institutes), and the Codex. The Corpus forms the basis of Latin jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical canon law: "ecclesia vivit lege romana," "the Church lives under Roman law"). It ensured the survival of Roman law, which would pass to the West in the 12th century and later to Eastern Europe, including Russia. It remains influential to this day.

As far as military campaigns, Justinian was generally successful; he was the last Byzantine emperor to have control over Rome and parts of the West. Like his Roman predecessors and Byzantine successors, Justinian initially engaged in war against Sassanid Persia in the Roman-Persian Wars. However, his primary military ambitions focused on the western Mediterranean, where his general Belisarius spearheaded the reconquest of parts of the territory of the old Roman Empire. Belisarius gained this task as a reward after successfully putting down the Nika riots in Constantinople, because of which Justinian considered fleeing the capital but remained in the city only on the advice of Theodora (according to Procopius). In 533 Belisarius reconquered North Africa from the Vandals, then advanced into Sicily and Italy, recapturing Rome (536) and the Ostrogothic capital at Ravenna (540) in what has become known as the Gothic War.Justinian and Orthodoxy

Perhaps the most noteworthy event occurred in 529 when the Academy in Athens (famous for being founded centuries earlier by Plato) was placed under state control by order of Justinian, effectively strangling this training school for Hellenism. Paganism was actively suppressed. The worship of Ammon at Augila in the Libyan desert was abolished, and so were the remnants of the worship of Isis on the island of Philae, in Egypt, and unrepentant Manicheans were executed in Constantinople. Justinian frequently sent out missionaries and converted numerous tribes. In Asia Minor alone, John, Bishop of Ephesus, converted 70,000 pagans.

Justinian also took a very firm stance in his support of Orthodoxy; he fought different heresies throughout his rule. At the beginning of his reign, he promulgated by law belief in the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation, and subsequently declared that he would deprive all disturbers of orthodoxy due process of law. He made the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed the sole symbol of the Church and accorded legal force to the canons of the four Ecumenical Councils. At the command of the sovereign, the Fifth Ecumenical Council was convened in the year 553, censuring the teachings of Origen and affirming the definitions of the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon. He also attempted to secure religious unity within the Empire through his (unsuccessful) dialogues with the non-Chalcedonians. He appointed Theodora, a convert from Monophysitism, as his special envoy to deal with those who rejected Chalcedon. Besides Monophysitism, other ecclesiastical tensions had begun to emerge between the East and the West; the "Three Chapters" controversy brought all of these to a head (cf. external links).

The Emperor was instrumental in the building of numerous churches. He gave orders to build 90 churches for the newly-converted and generously supported church construction within the Empire. The finest structures of the time are considered to be the monastery at Sinai, and the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Under St. Justinian many churches were built dedicated to the Theotokos. Since he had received a broad education, St. Justinian assiduously concerned himself with the education of clergy and monks, ordering them to be instructed in rhetoric, philosophy, and theology. He neglected no opportunity for securing the rights of the Church and clergy, for protecting and extending monasticism: his law codes contain many enactments regarding donations, foundations, and the administration of ecclesiastical property; election and rights of bishops, priests, and abbots; monastic life, residential obligations of the clergy, conduct of divine service, and episcopal jurisdiction.Justinian's standardization of the Divine Liturgy included introducing the Cherubic Hymn, and two oft-used troparia of the Church, Only Begotten Son and O Gladsome Light are traditionally accredited to him.

In his personal life, St. Justinian was strictly pious, and he fasted often. During Great Lent he would not eat bread nor drink wine, but lived on only water and vegetables. He is also remembered for promoting the idea of "symphony" between church and state.

However, Justinian is often criticized by secular sources as a despot. Even some dissent occurs in Orthodox Holy Tradition. For example, the hagiography of St. Eutychius paints a more complicated portrait of the Emperor:

- "After the death of the holy Patriarch Menas, the Apostle Peter appeared in a vision to the emperor Justinian and, pointing his hand at Eutychius, said, 'Let him be made your bishop.' At the very beginning of his patriarchal service, St Eutychius [not Justinian himself] convened the Fifth Ecumenical Council (553), at which the Fathers condemned the heresies cropping up and anathematized them. However, after several years a new heresy arose in the Church: Aphthartodocetism [asartodoketai] or "imperishability" which taught that the flesh of Christ...[was] not capable of suffering. St Eutychius vigorously denounced this heresy, but the emperor Justinian himself inclined toward it, and turned his wrath upon the saint. By order of the emperor, soldiers seized the saint in the church, removed his patriarchal vestments, and sent him into exile to an Amasean monastery (565)."[1]

However, Father Asterios Gerostergios in his book Justinian the Great: The Emperor and Saint, refutes the assertion that Justinian succumbed in his last years to the heresy of aphthartodocetism. It is commonly accepted that, after a lengthy reign in which Justinian spared no effort to try to bring the Monophysites back into the fold of the Orthodox Church, people were weary of the aged emperor. Thus, it is commonly asserted that Justinian adhered to the aphthartodocetist heresy, which was essentially an extreme form of Monophysitism, and deposed Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople for his supposed refusal to conform to this teaching.

Justinian's supposed decree imposing aphthartodocetism was not preserved, and the only contemporary source that refers to it is the testimony of the historian Evagrius. Most historians have accepted the information of Evagrius as true, reasoning that Justinian had either converted to the heresy at the end of his life or had succumbed to senility. These scholars thus relate the decree to the depositions of both Eutychius and Anastasius, patriarch of Antioch. Father Gerostergios states:

- That they were deposed because of their refusal to accept the edict we do not believe to be true because of the following reasons:

- 1. The bishop of Northern Africa, Victor, an enemy of the Emperor, mentions the deposition of Eutychius in his Chronicle, but does not give any reasons for the deposition. If he really knew anything about a new edict, and if, further, he knew of Justinian's acceptance of the aphthartodocetistic heresy, not only would he certainly have mentioned it, but he would also have emphasized the event, in order to defame Justinian's exiling and imprisoning him.

- 2. If Eutychius had been deposed for this reason, his successor, John the Scholastic, would have had to accept such a decree. We have absolutely no information concerning his acceptance of the edict, nor any testimony that he accepted aphthartodocetism. On the contrary, Pope [Saint] Gregory the Great, who was then the papal representative in Constantinople, praises the new patriarch, John, for his holiness and Orthodoxy.

- 3. The same Pope Gregory praises Justinian for his Orthodoxy and he makes no mention of the edict. He says that Patriarch Eutychius was an Origenist. For this reason, W. H. Hutton and A. Knecht have stated: this was the cause for Eutychius' deposition.

- 4. When Patriarch Eutychius returned to the throne of Constantinople in 577, he did not mention the reasons for his dethronement.

- 5. Bishop John of Ephesus, contrary to Evagrius, makes no mention of what transpired in Antioch concerning the deposition of Anastasius. …

- For all the above reasons, we can only conclude that Justinian never issued or planned to issue an edict imposing aphthartodocetism. Such an act would have been in antithesis to his whole previous theological work, and it is clear that it would not have helped the overall purpose of unification. Moreover, such a complete change at such an advanced age, we believe to be a totally unnatural thing. With regard to the deposition of the two mentioned Patriarchs, we believe that it was not related to such an edict, because there is no basis for such a conclusion from the contemporary sources. We are of the opinion that their deposition was due to other reasons, probably to their failure to obey the old Emperor. [2]

| Justinian | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Justin I |

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor 527-565 |

Succeeded by: ? |

Sources and external links

- Justinian I at Wikipedia

- St Justinian the Emperor (OCA)

- The Three-Chapter Controversy at Wikipedia

- University of Kansas Medieval History: Reign of Justinian, 527-565

- Orthodox America: Justinian the Great, Emperor and Saint (ROCOR)

- Roman Emperors: Justinian (A very detailed history.)

- Medieval Sourcebook: Excerpts from Procopius' Secret History of Justinian and his Court (Here Procopius slanders both Justinian and Theodora with vicious abandon.)

- Come and See Icons: Justinian

- earlychurch.org: Justinian I (Very pro-Justinian and the Church.)