Difference between revisions of "Pax Romana"

m (link) |

m (link) |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

==Summary== | ==Summary== | ||

| − | According to the deeper understanding of the Church fathers, ''Pax Romana'' becomes almost a metaphor<ref>Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them.</ref> and a vehicle for ''Pax Christi''. Metropolitan [[Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya]] has written that "it was the ''pax romana'' which accounted in no small degree to the amazing rapidity with which the Christian faith was disseminated in every territory under Roman rule."<ref>[[Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya]]. ''“Orthodoxy in Britain: Past, Present, and Future.”'' In: John Behr, Andrew Louth, Dimitri Conomos (eds.). '''Abba, The Tradition of Orthodoxy in the West: Festschrift for Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia.''' Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2003. pp.135-155.</ref> | + | According to the deeper understanding of the Church fathers, ''Pax Romana'' becomes almost a metaphor<ref>Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them.</ref> and a vehicle for ''Pax Christi''. Metropolitan [[Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya]] has written that "it was the ''pax romana'' which accounted in no small degree to the amazing rapidity with which the Christian faith was disseminated in every territory under Roman rule."<ref>[[Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya]]. ''“Orthodoxy in Britain: Past, Present, and Future.”'' In: John Behr, [[Andrew Louth]], Dimitri Conomos (eds.). '''Abba, The Tradition of Orthodoxy in the West: Festschrift for Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia.''' Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2003. pp.135-155.</ref> |

In the [[New Testament]], the [[Apostle Luke]], writing in the [[Acts of the Apostles|Book of Acts]] does not present the Roman Imperial order and its officers in as negative a light as does the [[Book of Revelation|Revelation of John]], but frequently in a positive light as well, highlighting a number of important factors: | In the [[New Testament]], the [[Apostle Luke]], writing in the [[Acts of the Apostles|Book of Acts]] does not present the Roman Imperial order and its officers in as negative a light as does the [[Book of Revelation|Revelation of John]], but frequently in a positive light as well, highlighting a number of important factors: | ||

Latest revision as of 01:30, September 19, 2011

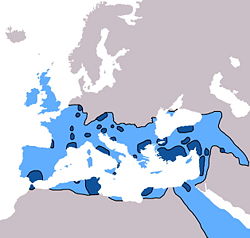

Pax Romana (Latin for "Roman peace", also Pax Augustus) was the long period of relative tranquillity throughout the Mediterranean world in the first and second centuries AD in the Roman Empire, from approximately 27 BC to 180 AD, or from the reign of Augustus to that of Marcus Aurelius.

Jesus Christ was born in the reign of Augustus, who, so to speak, fused together into one monarchy the many populations of the earth. Theological connections have been drawn by some Church fathers between the Pax Romana, and the Divine Providence of God which is thought to have effected it, in order to facilitate the spread of the Gospel of Christ, and through it, the true peace (pax) of God on earth, or Pax Christi.

In addition, the Pax Romana was also a phenomenon that occured especially in preparation for the first coming of the Lord on earth, alluded to in the Holy Scriptures where He is called the "Prince of Peace" (Isaiah 9:6-7, NKJV).

Contents

Pax Romana

The concept of Pax Romana as a historical phenomenon was first presented by English historian Edward Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, proposing a period of moderation and peace under Augustus and his successors.

The Age of Augustus was celebrated by the poets (especially Virgil) as a new era–the dawn of the age of gold. The empire was expanding in every area: law, culture, arts, humanities, military might, religious revival. The economy boomed, the temples were full–any and every new cult had opportunity to erect a temple in Rome. Reform was in the air–reform of manners–reform of religion–reform of the republic.[1]

Augustus laid the foundation for this period of concord, which also extended to North Africa and Persia.[2] Gibbon lists the Roman conquest of Britain under Claudius and the conquests of Trajan as exceptions to this policy of moderation, and places the end of the period at the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD.

The Pax Romana witnessed the great Romanization of the western world, including the spread of the legal system that brought law and order to the provinces, and which forms the basis of many western court systems today.[3] The arts and architecture flourished, along with commerce and the economy. The networks of good and safe roads and sea routes was greatly improved, there were free movements of peoples and mixing of cultures, as well as tolerance of foreign cults.[4] The Roman alphabet became the basis for the western world alphabet, and aqueducts brought water from the mountains to Roman cities.[5]

The Romans called the Pax Romana a "Time of Happiness." It was the fulfillment of Rome's mission - the creation of a world-state that provided peace, security, ordered civilization, and the rule of law. The cities of the Roman Empire served as centers of Greco-Roman civilization, which spread to the furthest reaches of the Mediterranean. Roman citizenship, gradually granted, was finally extended to virtually all free men by an edict in A.D. 212.[6]

Pax Romana as a Divine Will (Pax Christi)

Doxastikon for Vespers of the Nativity

The Doxastikon for Vespers of the Nativity, ascribed to the ninth-century nun Kassiani, proclaims a direct connection between the world-empire of Rome and the recapitulation of humanity in Christ. Pax Romana is thus made to coincide with Pax Christi[7]:When Augustus reigned alone upon earth, the many kingdoms of men came to end: and when Thou wast made man of the pure Virgin, the many gods of idolatry were destroyed. The cities of the world passed under one single rule; and the nations came to believe in one sovereign Godhead. The peoples were enrolled by the decree Caesar; and we, the faithful, were enrolled in the Name of the Godhead, when Thou, our God, wast made man. Great is Thy mercy: Glory to Thee.[8]

Eusebius of Caesarea

In addition, the early fourth century Church father Eusebius of Caesarea writes that by the express appointment of God, two roots of blessing, the Roman empire, and the doctrine of Christian piety, sprang up together for the benefit of men:

When that instrument of our redemption, the thrice holy body of Christ, which proved itself superior to all Satanic fraud, and free from evil both in word and deed, was raised, at once for the abolition of ancient evils, and in token of his victory over the powers of darkness; the energy of these evil spirits was at once destroyed. The manifold forms of government, the tyrannies and republics, the siege of cities, and devastation of countries caused thereby, were now no more, and one God was proclaimed to all mankind. At the same time one universal power, the Roman empire, arose and flourished, while the enduring and implacable hatred of nation against nation was now removed: and as the knowledge of one God, and one way of religion and salvation, even the doctrine of Christ, was made known to all mankind; so at the self-same period, the entire dominion of the Roman empire being vested in a single sovereign, profound peace reigned throughout the world. And thus, by the express appointment of the same God, two roots of blessing, the Roman empire, and the doctrine of Christian piety, sprang up together for the benefit of men.[9]

Origen

The early third century father Origen of Alexandria was a prolific writer and essentially a Biblical scholar who strenuously affirmed the inspiration, integrity and canonicity of Scriptures. He recognized in Biblical texts a literal, moral, and allegorical sense and became famous for applying the last one.[10] He also identifies the Divine Providence of God working through the Pax Romana in order to effect the spread of the Gospel of Christ and with it the true peace of God on earth or Pax Christi.

For righteousness has arisen in His days, and there is abundance of peace, which took its commencement at His birth, God preparing the nations for His teaching, that they might be under one prince, the king of the Romans, and that it might not, owing to the want of union among the nations, caused by the existence of many kingdoms, be more difficult for the apostles of Jesus to accomplish the task enjoined upon them by their Master, when He said, "Go and teach all nations." Moreover it is certain that Jesus was born in the reign of Augustus, who, so to speak, fused together into one monarchy the many populations of the earth. Now the existence of many kingdoms would have been a hindrance to the spread of the doctrine of Jesus throughout the entire world; not only for the reasons mentioned, but also on account of the necessity of men everywhere engaging in war, and fighting on behalf of their native country, which was the case before the times of Augustus, and in periods still more remote,...How, then, was it possible for the Gospel doctrine of peace, which does not permit men to take vengeance even upon enemies, to prevail throughout the world, unless at the advent of Jesus a milder spirit had been everywhere introduced into the conduct of things?[11]

It may also be noted that later on in the Roman Empire, major codifications of Roman law such as the Codex Theodosianus (AD 438), and the Codex Justianianus (AD 529-534) saw the introduction of Christian principles formalized into law. These deeply influenced the Canon Law of the Western Church and the civil law of Medieval Europe.

Biblical

The prophecy in Isaiah 9:5-6 (Septuagint) refers to the coming of the Lord on earth[12]:

For unto us a Child is born, unto us a Son is given; and the government will be upon His shoulder. His name will be called the Angel of Great Counsel, for I shall bring peace upon the rulers, peace and health by Him. Great shall be His government, and of His peace there is no end. His peace shall be upon the throne of David and over His kingdom, to order and establish it with righteousness and judgment, from that time forward and unto ages of ages. The zeal of the Lord of hosts shall perform this.[13]

In Jeremiah 34:3-6 (Septuagint), the Lord affirms His ownership of the earth:

'Thus says the Lord God of Israel to your masters: "I made the earth by My great strength and with my high arm, and I will give it to whomever it may seem good in My eyes. I gave the earth to Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon to serve him: and I gave the wild beasts of the field to him to work for him. But the nation and kingdom, whoever will not put their neck under the yoke of king of Babylon, I will visit them with the sword and with famine," says the Lord, "until they come to an end by his hand..."' [14]

In John 19:11 the Lord Himself again affirms this when he speaks to Pontius Pilate saying:

"You could have no power at all against Me unless it had been given you from above."[15]

Historical Criticism

Given the above, one of the ironic trends during the Pax Romana was that Christianity was widely persecuted throughout the Roman empire. Although the spread of the Imperium Romanum was associated with the idea of Pax Romana, the Pax Romana in its turn was also associated with the compulsory recognition of the Roman emperor cult, in spite of all the religious tolerance which we know the Romans to have exercised.[16] In spite of this however the overriding trend was the growth and mission of the Church of Christ, and its ultimate victory as the Roman Empire was eventually Christianized.

Also, despite the term the period was not without armed conflict, as Emperors frequently had to quell rebellions. Both border skirmishes and Roman wars of conquest also happened during this period. Trajan embarked on a series of campaigns against the Parthians during his reign and Marcus Aurelius spent almost the entire last decade of his rule fighting against the Germanic tribes. Nonetheless the interior of the Empire remained largely untouched by warfare. The Pax Romana was an era of relative tranquility in which Rome endured neither major civil wars, such as the perpetual bloodshed of the third century AD, nor serious invasions, or killings, such as those of the Second Punic War three centuries prior.

Summary

According to the deeper understanding of the Church fathers, Pax Romana becomes almost a metaphor[17] and a vehicle for Pax Christi. Metropolitan Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya has written that "it was the pax romana which accounted in no small degree to the amazing rapidity with which the Christian faith was disseminated in every territory under Roman rule."[18]

In the New Testament, the Apostle Luke, writing in the Book of Acts does not present the Roman Imperial order and its officers in as negative a light as does the Revelation of John, but frequently in a positive light as well, highlighting a number of important factors:

For Luke, although the Pax Romana is only a dialectical[19] phenomenon that soon has to be replaced by the Pax Christi, it is still better than its opposite, be it wars between nations or anarchy and suffering that would result from revolutionary upheavals....Luke's reports of the imperial military, administration, and judiciary sometimes functioning to protect Christian missionaries, and his reports of Paul's use of his citizenship, his insistence on the proper execution of Roman law (Acts 16:19-39; 25:9-10), and his appeal to Caesar (Acts 25:10-12) seem to reflect Luke's relative appreciation of the Roman imperial order, in spite of its essential diabolic nature and occasional failures.[20]

Jesus Christ and not Augustus is the author of peace, and the bringer of God's gospel of peace. In the Apostle Peter's sermon to the Roman officer Cornelius at Caesarea in Acts 10:34-43, he clearly intends to make Cornelius and his Roman colleagues understand that "Jesus Christ - He is the Lord of all", not Augustus or his sucessor, but the Lord who has brought the gospel of peace.[21]

See also

External Links

Wikipedia

- Ara Pacis

- Christianization: Early Christianity (pre-Nicaean)

- Christianization: Late Antiquity (4th-6th centuries) (Christianization of the Roman Empire).

Further Reading

- Ramsay MacMullen. Christianizing the Roman Empire: (A.D. 100-400). New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984. ISBN 9780300036428

- Seyoon Kim. "An Appreciation of Pax Romana." in: Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Sept. 15 2008. pp.177-179. ISBN 978-0802860088

References

- ↑ James T. Dennison, Jr. Pax Romana, Pax Christi: Luke 2:1-20. The Online Journal of Biblical Theology. April 23, 1987.

- ↑ "Pax Romana." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ↑ Pax Romana at UNRV History

- ↑ Seyoon Kim. "An Appreciation of Pax Romana." in: Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Sept. 15 2008. pp.179.

- ↑ Pax Romana at Conservapedia.

- ↑ Marvin Perry, Margaret Jacob, James Jacob. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society - from 1600. Volume 2 of Western Civilization. 9th Edition. Cengage Learning, 2008. p. xxiv.

- ↑ Dimitri E. Conomos. Byzantine Hymnography and Byzantine Chant. Hellenic College Press: Brookline, Massachsetts, 1984. pp.10

- ↑ Dimitri E. Conomos. Byzantine Hymnography and Byzantine Chant. Hellenic College Press: Brookline, Massachsetts, 1984. pp.10

- ↑ Eusebius Pamphilus of Caesarea. Oration in Praise of the Emperor Constantine Pronounced on the Thirtieth Anniversary of His Reign. Ch.16, 3-4. The Early Church Fathers (38 Vols.)

- ↑ Rev. Dr. Nicon D. Patrinacos (M.A., D.Phil. (Oxon)). A Dictionary of Greek Orthodoxy - Λεξικον Ελληνικης Ορθοδοξιας. Light & Life Publishing, Minnesota, 1984. pp.380.

- ↑ Origen. Against Celsus. Book 2, Ch.30. The Early Church Fathers (38 Vols.)

- ↑ He is referred to as the "Prince of Peace" in other translations.

- ↑ The Orthodox Study Bible. St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology. Elk Grove, California, 2008. Isaiah 9:5-6. pp.1065-1066

- ↑ The Orthodox Study Bible. St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology. Elk Grove, California, 2008. Jeremiah 34:3-6. pp.1147.

- ↑ The Orthodox Study Bible. St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology. Elk Grove, California, 2008. John 19:11. pp.1462.

- ↑ Jürgen Moltmann, R. A. Wilson. The crucified God: the cross of Christ as the foundation and criticism of Christian theology. Fortress Press, 1993. p.136.

- ↑ Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them.

- ↑ Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya. “Orthodoxy in Britain: Past, Present, and Future.” In: John Behr, Andrew Louth, Dimitri Conomos (eds.). Abba, The Tradition of Orthodoxy in the West: Festschrift for Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2003. pp.135-155.

- ↑ Dialectic: Discussion and reasoning by dialogue as a method of intellectual investigation.

- ↑ Seyoon Kim. "An Appreciation of Pax Romana." in: Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Sept. 15 2008. pp.177-178.

- ↑ Seyoon Kim. Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Sept. 15 2008. pp.83.

Sources

- Dimitri E. Conomos. Byzantine Hymnography and Byzantine Chant. Hellenic College Press: Brookline, Massachsetts, 1984.

- Eusebius Pamphilus of Caesarea. Oration in Praise of the Emperor Constantine Pronounced on the Thirtieth Anniversary of His Reign. Ch.16, 3-4. The Early Church Fathers (38 Vols.)

- Origen. Against Celsus. Book 2, Ch.30. The Early Church Fathers (38 Vols.)

- "Pax Romana." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- James T. Dennison, Jr. Pax Romana, Pax Christi: Luke 2:1-20. The Online Journal of Biblical Theology. April 23, 1987.

- Jürgen Moltmann, R. A. Wilson. The crucified God: the cross of Christ as the foundation and criticism of Christian theology. Fortress Press, 1993.

- Marvin Perry, Margaret Jacob, James Jacob. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society - from 1600. Volume 2 of Western Civilization. 9th Edition. Cengage Learning, 2008.

- Seyoon Kim. "An Appreciation of Pax Romana." in: Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Sept. 15 2008. pp.177-179.

- Pax Romana at Wikipedia.

- Pax Romana at Conservapedia.

- Pax Romana at UNRV History.

- Rev. Dr. Nicon D. Patrinacos (M.A., D.Phil. (Oxon)). A Dictionary of Greek Orthodoxy - Λεξικον Ελληνικης Ορθοδοξιας. Light & Life Publishing, Minnesota, 1984.

- The Orthodox Study Bible. St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology. Elk Grove, California, 2008.