Difference between revisions of "Book of Revelation"

m (→Methods of Interpretation: sp) |

m (→Literary Devices: sp) |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Another fairly recent and somewhat theologically liberal school of thought pays special attention to Revelation 19.10, in which an angel tells the author, "The spirit of prophecy is the testimony of Jesus Christ." In this light, some argue, Revelation is a depiction of the story of Jesus, using symbols related to Jesus and the Jewish traditions which he both followed and fulfilled. Typically, this school borrows heavily from the Preterist and Idealist schools, but sometimes from the Futurist and Historicist schools of interpretation as well. | Another fairly recent and somewhat theologically liberal school of thought pays special attention to Revelation 19.10, in which an angel tells the author, "The spirit of prophecy is the testimony of Jesus Christ." In this light, some argue, Revelation is a depiction of the story of Jesus, using symbols related to Jesus and the Jewish traditions which he both followed and fulfilled. Typically, this school borrows heavily from the Preterist and Idealist schools, but sometimes from the Futurist and Historicist schools of interpretation as well. | ||

| − | ==Literary | + | ==Literary devices== |

| − | Symbolism plays a key role in the book of Revelation, and is modeled after | + | Symbolism plays a key role in the book of Revelation, and is modeled after similar works, particularly the Book of Daniel, which seems to portray concrete events with highly-developed symbols. Portions of other Old Testament works follow this pattern, such as Ezekiel and Jeremiah. As much as 90% of Revelation's text is borrowed from previous Jewish texts, the Talmud, and is often reframed. Accordingly, most of the scenes and symbols used in Revelation utilize preexisting Jewish imagery, and often seem to represent Christian events from a Jewish perspective. |

| − | Parallel structure also plays a large part in Revelation as a work of literature. For example, the story of two witnesses in chapter 11, raised to life by the Spirit of God, strongly parallels the following story in chapter 12, in which symbols opposite the witnesses | + | Parallel structure also plays a large part in Revelation as a work of literature. For example, the story of two witnesses in chapter 11, raised to life by the Spirit of God, strongly parallels the following story in chapter 12, in which symbols opposite the witnesses—the Dragon, specifically, and others by extension—are raised to life by an anti-spirit opposing God. |

| − | There are a number of possible explanations for both of these devices. Orthodox tradition identifies 85 AD as the time of Revelation's final | + | There are a number of possible explanations for both of these devices. Orthodox tradition identifies 85 AD as the time of Revelation's final creation, placing the author and his audience in a time of intense persecution under the Roman Emperor Domitian. Other scholars alternatively suggest the Neronian persecutions as the time of Revelation's creation. In either case, it appears as though Revelation was written during a historical period hostile to the message and methods of Christianity as a whole. It may be that Revelation's author both adopted his symbolic style and utilized a tightly-knit parallel structure to obscure the Christianity story enough to save it from destruction yet still communicate its central message. Only those already familiar with the Jewish symbolism from which he borrows so heavily will understand the original meanings of those symbols and comprehend the new message which he is trying to communicate. |

| − | Another alternative or | + | Another alternative or additional possibility is that Revelation forces would-be Christian scholars to tackle its very intricate and complicated imagery, forcing them to delve into the Jewish history, tradition, and texts from which Christianity springs. This, too, fits the historical situation of the early Church, which moved further and further from its Jewish roots as Christianity became more and more Hellenized; no matter what school of thought one favors, a mastery of the orthodox Jewish texts is critical to a full understanding of the Revelator's message. |

==Common question: ''Pre- or post-millennialism''== | ==Common question: ''Pre- or post-millennialism''== | ||

Revision as of 20:44, June 20, 2008

The Apocalypse of St. John, or the Book of Revelation, is the last book of the Bible, and in most traditions is believed to cover those events which surround the end of the world, and the Last Judgement.

"We must have humility when approaching Scripture. Even some of the Church's greatest and most philosophically sophisticated saints stated that some passages were difficult for them. We must therefore be prepared to admit that our interpretations may be wrong, submitting them to the judgment of the Church." —from the article on Hermeneutics

Contents

History

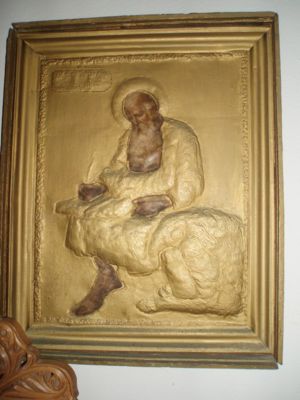

According to Tradition, the Apocalypse was written by St. John the Theologian, one of the Twelve Apostles, while he was in exile on the island of Patmos towards the end of his life.

The book finally was accepted into the Canon after much dispute.

Methods of interpretation

There are a variety of ways to interpret the book of Revelation, and many of these methods overlap.

Some read the book of Revelation as entirely symbolic. This type of interpretation is often called Idealism, and "translates" the symbols found in the book as universal symbols depicting the clash between good and evil.

Others read Revelation as a book containing symbolism regarding events entirely contained in the past--in this school of interpretation, Revelation is about what has already happened, and not what will happen in the future. This is often called the Preterist (from Latin, meaning "Past") school of interpretation. In this school of thought, Revelation uses preexisting Jewish symbolism the depict and explain the immediate and pressing concerns of the author.

Still others read the book as a book of speculative prophecy, literally portraying the apocalyptic end of time in which the glorified Christ will come to earth and usher in Judgment Day. While not all people who adopt this Futurist method insist on interpreting every symbol as literally as possible, this is by far the most common interpretation in fundamentalist camps. Another method, similar in methodology, is the Historicist school, which identifies some of Revelation as occurring in the past and some as occurring in the future—often, this method applies the imagery of Revelation to major historical events, i.e., equating the plague of locusts with the spread of Islam throughout medieval Europe.

Another fairly recent and somewhat theologically liberal school of thought pays special attention to Revelation 19.10, in which an angel tells the author, "The spirit of prophecy is the testimony of Jesus Christ." In this light, some argue, Revelation is a depiction of the story of Jesus, using symbols related to Jesus and the Jewish traditions which he both followed and fulfilled. Typically, this school borrows heavily from the Preterist and Idealist schools, but sometimes from the Futurist and Historicist schools of interpretation as well.

Literary devices

Symbolism plays a key role in the book of Revelation, and is modeled after similar works, particularly the Book of Daniel, which seems to portray concrete events with highly-developed symbols. Portions of other Old Testament works follow this pattern, such as Ezekiel and Jeremiah. As much as 90% of Revelation's text is borrowed from previous Jewish texts, the Talmud, and is often reframed. Accordingly, most of the scenes and symbols used in Revelation utilize preexisting Jewish imagery, and often seem to represent Christian events from a Jewish perspective.

Parallel structure also plays a large part in Revelation as a work of literature. For example, the story of two witnesses in chapter 11, raised to life by the Spirit of God, strongly parallels the following story in chapter 12, in which symbols opposite the witnesses—the Dragon, specifically, and others by extension—are raised to life by an anti-spirit opposing God.

There are a number of possible explanations for both of these devices. Orthodox tradition identifies 85 AD as the time of Revelation's final creation, placing the author and his audience in a time of intense persecution under the Roman Emperor Domitian. Other scholars alternatively suggest the Neronian persecutions as the time of Revelation's creation. In either case, it appears as though Revelation was written during a historical period hostile to the message and methods of Christianity as a whole. It may be that Revelation's author both adopted his symbolic style and utilized a tightly-knit parallel structure to obscure the Christianity story enough to save it from destruction yet still communicate its central message. Only those already familiar with the Jewish symbolism from which he borrows so heavily will understand the original meanings of those symbols and comprehend the new message which he is trying to communicate.

Another alternative or additional possibility is that Revelation forces would-be Christian scholars to tackle its very intricate and complicated imagery, forcing them to delve into the Jewish history, tradition, and texts from which Christianity springs. This, too, fits the historical situation of the early Church, which moved further and further from its Jewish roots as Christianity became more and more Hellenized; no matter what school of thought one favors, a mastery of the orthodox Jewish texts is critical to a full understanding of the Revelator's message.

Common question: Pre- or post-millennialism

The view of the Orthodox Church can best be described as "amillenialist"; that is, holding to the teaching that the thousand years mentioned in the Apocalypse refers to the current age of the Church.

The Last Judgment

The Soul after Death by Fr. Seraphim Rose is an excellent reference for this.

Sources

- Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, Fr. Seraphim Rose

- The Soul after Death, Fr. Seraphim Rose

Additional notes on the Apocalypse from the American Tract Society Bible Dictionary

Apocalypse signifies revelation, but is particularly referred to the revelations which John had in the isle of Patmos, whither he was banished by Domitian. Hence it is another name for the book of Revelation. This book belongs, in its character, to the prophetical writings, and stands in intimate relation with the prophecies of the Old Testament, and more especially with the writings of the later prophets, as Ezekiel, Zechariah, and particularly Daniel, inasmuch as it is almost entirely symbolical. This circumstance has surrounded the interpretation of this book with difficulties, which no interpreter has yet been able fully to overcome. As to the author, the weight of testimony throughout all the history of the church is in favor of John, the beloved apostle. As to the time of its composition, most commentators suppose it to have been written after the destruction of Jerusalem, about A.D. 96; while others assign it an earlier date.

It is an expanded illustration of the first great promise, "The seed of the woman shall bruise the head of the serpent." Its figures and symbols are august and impressive. It is full of prophetic grandeur, and awful in its hieroglyphics and mystic symbols: seven seals opened, seven trumpets sounded, seven vials poured out; mighty antagonists and hostile powers, full of malignity against Christianity, and for a season oppressing it, but at length defeated and annihilated; the darkened heaven, tempestuous sea, and convulsed earth fighting against them, while the issue of the long combat is the universal reign of peace and truth and righteousness-the whole scene being relieved at intervals by a choral burst of praise to God the Creator, and Christ the Redeemer and Governor. Thus its general scope is intelligible to all readers, or it could not yield either hope or comfort. It is also full of Christ. It exhibits his glory as Redeemer and Governor, and describes that deep and universal homage and praise which the "Lamb that was slain" is forever receiving before the throne. Either Christ is God, or the saints and angels are guilty of idolatry.

"To explain this book perfectly," says Bishop Newton, "is not the work of one man, or of one age; probably it never will be clearly understood till it is all fulfilled."

(The American Tract Society Bible Dictionary is a dictionary of the Holy Bible, for general use in the study of the scriptures; with engravings, maps, and tables. Its copyrights have expired. Previously published in New York by the American Tract society [c1859]. Rand, W. W. (William Wilberforce), 1816-1909, ed.)