Difference between revisions of "Code of Justinian"

m (→External Links) |

m (interwiki ro) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

[[Category:Church Life]] | [[Category:Church Life]] | ||

[[Category:Canon Law]] | [[Category:Canon Law]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[ro:Codul lui Iustinian]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:43, November 10, 2011

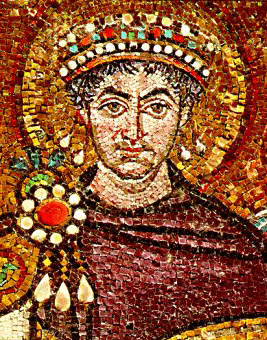

The Codex Justinianus (Code of Justinian) was the first of four parts of the Corpus Juris Civilis ("Body of Civil Law"),[note 1] a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence that was issued from 529 to 534 AD by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor, who achieved lasting influence for his judicial reforms via the summation of all Roman law.

This code compiled in Latin all of the existing imperial constitutiones (imperial pronouncements having the force of law), back to the time of emperor Hadrian in the second century. It used both the Codex Theodosianus (438 AD) and the fourth-century collections embodied in the Codex Gregorianus and Codex Hermogenianus, which provided the model for division into books, that were divided into titles. These codices had developed authoritative standing.[1] The "Corpus Juris Civilis" was directed by Tribonian, an official in Justinian's court, and was distributed in three parts, with a fourth part (Novellae) being added later:

- "Codex Justinianus" (529) compiled all of the extant imperial constitutiones from the time of Hadrian. It used both the Codex Theodosianus and private collections such as the Codex Gregorianus and Codex Hermogenianus.

- "Digesta" , or Pandectae , (533), was a compilation of passages from juristic books and law commentaries of the great Roman jurists of the classical period, mostly dating back to the second and third centuries, along with current edicts. It constituted both the current law of the time, and a turning point in Roman Law: from then on the sometimes contradictory case law of the past was subsumed into an ordered legal system.

- "Institutiones" , or 'Elements' (533), a modified codification of the celebrated Roman jurist Gaius' legislation. The Institutes were intended as sort of legal textbook for law schools and included extracts from the two major works. It was made as the Digest neared completion, by Tribonian and two professors, Theophilus and Dorotheus.

- "Novellae" , a number of new constitutions that were passed after 534, issued mostly in Greek. They were later re-worked into the Syntagma, a practical lawyer's edition, by the Byzantine jurist Athanasios of Emesa during the years 572–77.

All four of these together formed Justinian's Corpus of Civil Law which deeply influenced the Canon Law of the Western Church and the civil law of Medieval Europe, especially since it was said that ecclesia vivit lege romana — the church lives under Roman law.[2] The Code's underlying claim that the emperor's will was supreme in all things made imperial control of the Church legal and thus deeply influenced the subsequent development of the Byzantine Church.

It remains influential to this day. By way of the Napoleonic Code (AD 1804), the Justinian Code reached Canada in the Province of Quebec, and was later introduced by French immigrants to Louisiana in the United States.[3]

Contents

Codex Justinianus

The Codex Justinianus (Code of Justinian, Justinian's Code) was the first part to be completed, on April 7, 529. It collects the constitutiones of the Roman Emperors. The earliest statute preserved in the code was enacted by Emperor Hadrian; the latest came from Justinian himself.

Legislation about religion

Numerous provisions serve to secure the status of Orthodox Christianity as the state religion of the empire, uniting Church and state, and making anyone who was not connected to the Christian church a non-citizen.

Laws against heresy

The very first law in the Codex requires all persons under the jurisdiction of the Empire to hold the holy Orthodox (Christian) faith. This was primarily aimed against heresies such as Arianism. This text later became the springboard for discussions of international law, especially the question of just what persons are under the jurisdiction of a given state or legal system.

Laws against paganism

Other laws, while not aimed at pagan belief as such, forbid particular pagan practices. For example, it is provided that all persons present at a pagan sacrifice may be indicted as if for murder.

Laws against Judaism

The principle of "Servitude of the Jews" (Servitus Judaeorum) was established by the new laws, and determined the status of Jews throughout the Empire for hundreds of years. The Jews were disadvantaged in a number of ways. They could not testify against Christians and were disqualified from holding a public office. Jewish civil and religious rights were restricted: "they shall enjoy no honors". The use of the Hebrew language in worship was forbidden. Shema Yisrael, sometimes considered the most important prayer in Judaism ("Hear, O Israel, YHWH our God, YHWH is one") was banned, as a denial of the Trinity. A Jew who converted to Christianity was entitled to inherit his or her father's estate, to the exclusion of the still-Jewish brothers and sisters. The Emperor became an arbiter in internal Jewish affairs. Similar laws applied to the Samaritans.

Corpus Juris Civilis Texts

Complete Three Volume Set in Latin

- Theodorus Mommsen, Rudolf Schoell, Wilhelm Kroll, & Paulus Krueger (eds.). Corpus Juris civilis, Editio Stereotypa Altera: Institutiones, Digesta, Codex Justinianus, Novellae & Opus Schoelli Morte Interceptum. (Three-Volume Set). Weidmann, 1895. ISBN B001NQ032U

- Corpus iuris civilis V.1. - Institutiones; Digesta (1889)

- Corpus iuris civilis V.2. - Codex Justinianus (1892)

- Corpus iuris civilis V.3. - Novellae (1895)

- Corpus Iuris Civilis (1877-1895). This is the version that Supreme Court Justice Fred H. Blume (+1971) employed in creating his translations of the Code and Novels. It has gone through several editions and reprintings, the most recent being 1993-2000. This version is accepted by scholars as the standard edition.

In English

- The Digest of Justinian, Volume 1 [Paperback]

- The Digest of Justinian, Volume 2 [Paperback]

- The Digest of Justinian, Volume 3 [Paperback]

- The Digest of Justinian, Volume 4 [Paperback]

- Justinian's Institutes [Paperback]

Notes

- ↑ The name "Corpus Juris Civilis" occurs for the first time in 1583 as the title of a complete edition of the Justinianic code by Dionysius Godofredus. (Kunkel, W. An Introduction to Roman Legal and Constitutional History. Oxford 1966 (translated into English by J.M. Kelly), p. 157, n.2.)

References

- ↑ George Long. In: William Smith, ed.. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. (London: Murray) 1875 (On-line text).

- ↑ Cf. Lex Ripuaria, tit. 58, c.1: "Episcopus archidiaconum jubeat, ut ei tabulas secundum legem romanam, qua ecclesia vivit, scribere faciat". ([1])

- ↑ Rev. Dr. Nicon D. Patrinacos (M.A., D.Phil. (Oxon)). A Dictionary of Greek Orthodoxy - Λεξικον Ελληνικης Ορθοδοξιας. Light & Life Publishing, Minnesota, 1984. pp.221.

Sources

- Rev. Dr. Nicon D. Patrinacos (M.A., D.Phil. (Oxon)). A Dictionary of Greek Orthodoxy - Λεξικον Ελληνικης Ορθοδοξιας. Light & Life Publishing, Minnesota, 1984. pp.221.

- Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Medieval Legal History: ROMAN LAW. (Paul Halsall, ORB sources editor).

- Corpus Juris Civilis at Wikipedia.

External Links

Wikipedia

- Byzantine law

- Roman law

- Littera Florentina (parchment codex of 907 leaves, being the closest survivor to an official version of the Pandects, the Digest of Roman law promulgated by Justinian I in 530–533.)