Church of the Holy Saviour in the Country (Istanbul,Turkey)

The Church of the Holy Saviour in the Country, (Greek: ἡ Ἐκκλησία του Ἅγιου Σωτῆρος ἐν τῃ Χώρᾳ, hē Ekklēsia tou Hagiou Sōtēros en tē Chōra), more popularly Chora Church, is a former Orthodox Christian church, now a museum, located in the Kariye neighborhood of Istanbul, Turkey. The church was converted into a mosque after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. Then, in mid-twentieth century, after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, it was again converted, this time into a museum, displaying its Byzantine art. The church is noted as a fine example of fourteenth century Byzantine Christian mosaic art.

Contents

[hide]History

When the original Chora Church was built early in the fifth century it was outside the walls of the city of Constantinople, that is in the countryside, from which it received its informal name of Chora, meaning in the country. The church was situated within the new walls around the city that emperor Theodosius II built later in that century. However, although now in the city, that is within the walls around the city, the church retained the name Chora. Through the following centuries the church was damaged by earthquakes and was largely abandoned.

During the years 1077 to 1081, the church was rebuilt by the mother-in-law of emperor Alexius I Comnenus, Maria Ducaena, in the form of an inscribed cross, a popular architectural style of the period. After having been again damaged by earthquakes, restoration work on the church was done in the twelfth century by Isaac Comnenus. During 1315 to 1321, a major reconstruction effort was commissioned by Theodore Metochites during which most of the mosaics and frescos seen today were added. The mosaics remain among the finest examples of the Palaeologian Renaissance.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Chora Church was converted into a mosque and given the name Kariye Carnil (Kariye Mosque). The images of the frescos and mosaics were plastered over and the building interior modified for muslim prayers. A minaret was built on the outside. Early in the twentieth century, the minaret toppled during an earthquake, and fell onto one of the domes, destroying it and its mosaics. While remaining a mosque, the building continued to deteriorate.

In 1948, a program was started by William Whittemore and Paul A. Underwood, from the Byzantine Institute of America and the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, to restore the building. As the restoration of the interior progressed, use of the building as a mosque was discontinued. In 1958, the Chora Church reopened as the Kariye (Chora) Museum.

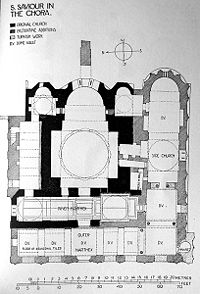

Architecture

The Chora Church is not as large as some of the other Byzantine era churches of Istanbul, but what it lacks in size, it makes up for in the beauty of its interior. The form of Chora Church is complex. The main body of the church, the naos, is oriented facing east to the altar and is covered by a large dome. To each side of the altar are two smaller apses, each covered by smaller domes. Entrance to the naos on the west is through a two part narthex, an external exonarthex and an internal esonarthex. There are two small domes over either end of the esonarthex. To the right of the naos/narthex assemblage is a side church or chapel called the parecclesion. The second largest dome on the church covers the mid portion of the parecclesion. The parecclesion was used as a mortuary chapel for family burials and memorials.

Mosaics

There are about 50 mosaic panels that date back to the beginning of the fourteenth century in the church. Most of these are in very good condition. Each of the four major sections of the church are covered with mosaics. Those in the external narthex generally relate to the life of Jesus. Those in the internal narthex generally relate to the Theotokos. The main frescos in the parecclesion are the Anastasia, the Resurrection of Christ, and the second coming of Christ.